The PKK is giving up armed struggle, but wants recognition of the Kurdish minority. If Erdoğan accepts, Turkey can save its democracy and resume rapprochement with the EU, and the change in policy would also have regional implications.

Recep Tayyip Erdoğan's efforts to consolidate his power at home, as well as his foreign policy, have led to both the erosion of his regime and the deterioration of Turkey's relations with its traditional partners.

The arrest of the Turkish opposition leader and a series of attacks against Kurdish militants suggest that, for the Erdoğan regime, maintaining power overrides external credibility.

The Trump administration's signals about a US policy toward Moscow, Ukraine, and the EU are causing concern in Russia's neighborhood, from the Black Sea to the Baltic Sea.

Putin believed that by invading Ukraine and engaging in wars in the East, he was restoring Russia's great power status. The result was Moscow's long-term loss of influence.

Donald Trump's return to the White House has generated fears about his approach to Russia and the conflict in Ukraine, as well as the economic relationship with the European Union. Veridica’s team of contributors has analyzed how Trump’s return to power is seen in Brussels and in Russia's neighboring countries - some of them ex-Soviet or ex-communist states, most of them members of the EU or NATO or with Euro-Atlantic aspirations.

The names floated for the incoming Trump administration suggest that the greater Middle East will remain a focus for Washington. An attention that Iran and Turkey do not like.

From the USA to China and Russia, from India to the Middle East, political leaders are over 70. Can they still make use of their experience to their advantage, or are they unable to adapt and have thus become a source of problems?

As the development of trade routes between the West and the East is in full swing, Iran and Turkey risk being overlooked due to their own policies, despite their strategic position between the two regions.

President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan's Islamist AKP party sustained a bitter defeat in the local election. Is Turkey heading for a “reset” and the end of the Erdoğan era?

Azerbaijan's authoritarian leader, Ilham Aliyev, was re-elected president after winning the Nagorno-Karabakh war and can turn his country into an energy and trade hub halfway between Asia and Europe.

The consolidation of Turkey’s presidential regime, to the detriment of the rule of law and in defiance of Western partners, will generate instability in the Black Sea region and trigger a wave of migrants towards the EU.

Turkey refused to condemn Hamas’ attack and criticized Israel in hopes of electoral gains for Erdoğan's Islamists. However, Turkey's regional interests will suffer.

The dismantling of the Nagorno Karabakh republic was the most important change in the South Caucus since Turkey (re)emerged as a powerhouse there. More changes might follow.

A century after its founding, the Turkish Republic is drifting further and further away from the secular values that formed its foundation, while ethno-religious nationalism is gaining ground.

After winning the election, president Erdoğan announced Turkey will stop vetoing Sweden’s NATO accession bid. What prompted this 180-degree shift and what did Turkey get in return?

After the latest elections, Turkey seems determined to continue its combative/aggressive policies, while Greece becomes increasingly important to NATO's south-eastern flank and the EU's energy security.

The victory of Erdoğan’s authoritarian and conservative regime is the victory of devout Turks who considered themselves repressed by the secular republican regimes of the last century.

On May 28, Turks will decide whether to consolidate the regime of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, the strongman of Turkey’s politics who has reigned unchallenged for the last 20 years, or to vote for Kemal Kiliçdaroğlu, seen as Turkey’s “Ghandi”, who fosters a return to old republican values.

Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and his party, AKP, will face the most difficult elections in the last twenty years. The economic crisis, the February 6 earthquake, the opposition coalition and the possible mobilization of the Kurds diminish Erdoğan's chances of staying in power. The end of the Erdoğan era does not mean that Turkey will become a liberal democracy – but there is a chance that it will

The February 6 quake could deal a heavy blow to the administration led by Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, commonly seen as the man responsible for the disregard of building safety codes. The Turkish president came under heavy criticism for the authorities’ sluggish response to this disaster, which affected primarily the Kurds and the Alevi. The quake might equally exert a heavy toll on Turkey’s foreign policy, considering that Ankara’s traditional enemies have shown solidarity with the Turkish people.

Recep Tayyip Erdoğan is trying to consolidate his regime by jockeying a third term at the helm of the country. The general elections this spring will take place amidst a severe economic crisis. To increase their odds, the Islamists have resorted to electoral handouts and sabotaging the opposition. The elections take place in a very special year: 2023 marks a century since Mustaka Kemal Atatürk proclaimed the republic, a republic which today is facing a full-blown crisis and is drifting further away from the vision of its founder.

Turkey has bombed Kurdish positions in Iraq and Syria in response to the bomb attack in Istanbul, warning this is just the beginning. A wider operation in Syria would help the Erdoğan regime draw attention away from the country’s economic troubles. Besides, it might also be a first step towards solving the refugee crisis. Russia, a country involved in the Syrian conflict, could turn a blind eye to Ankara’s moves because it is interested in exporting natural gas via pipelines transiting Turkey.

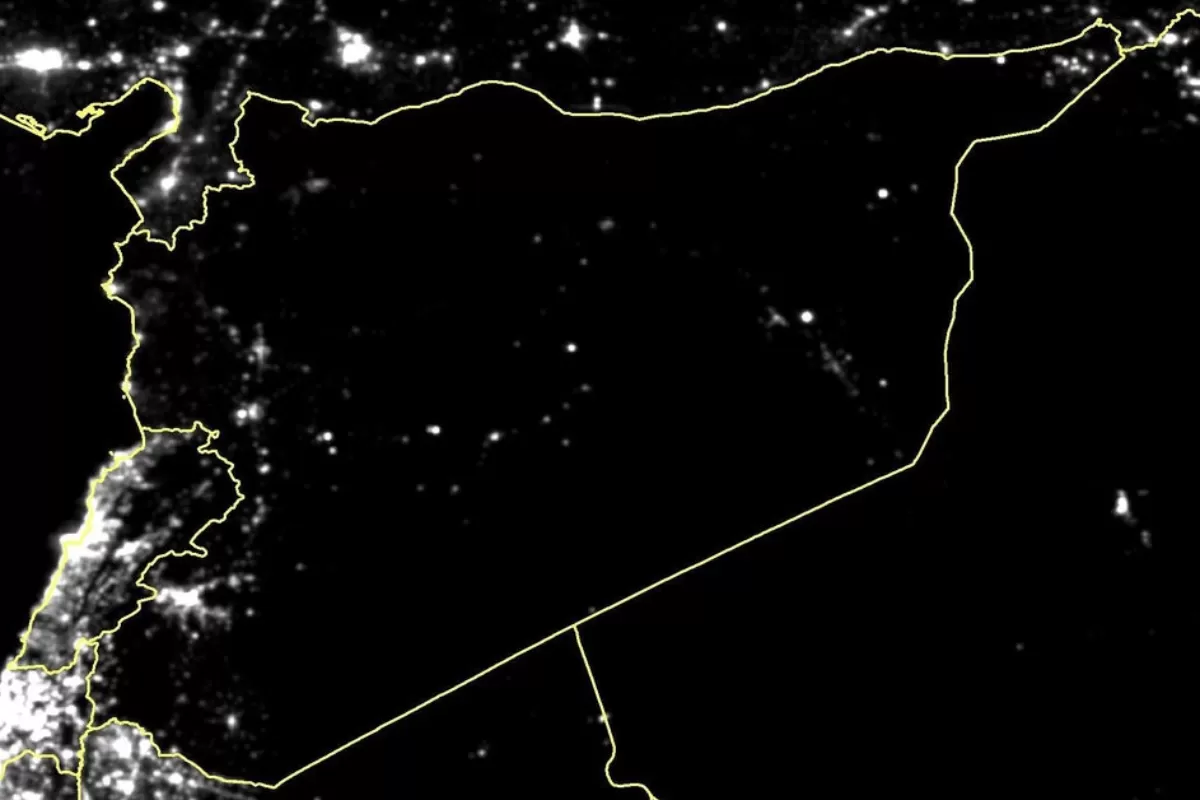

Syria remains a country ravaged by conflict and a deep humanitarian crisis, a place of conflicting interests of multiple state and non-state actors, says the Chargé d'Affaires of the European Union to Syria, Dan Stoenescu*. In an interview for TVR and Veridica, Dan Stoenescu explained that, although it doesn’t recognize the Assad regime, the EU keeps communication channels open in order to provide assistance to the Syrian people. The EU official also spoke about the link between the war in Syria and the one in Ukraine.

The relationship between Turkey and Greece is once again marked by tension, and Ankara's tough statements have made some observers wonder if this time there will be military confrontations. However, the current crisis seems to be related to the efforts made by the regime in Ankara to divert attention from domestic problems rather than to the old rivalry between the two countries.

Turkey is threatening with a new offensive in Syria, invoking the danger of Kurdish terrorism. This danger appears to be low in Mardin, near the Kurdish-Syrian border, which confirms expert analyses according to which the Erdoğan regime is in fact trying to divert attention from the economic crisis it is facing.

Turkey’s threats to veto Sweden and Finland’s NATO accession were interpreted as an attempt to secure certain concessions from the West in the context of economic difficulties at home. The previous policies of the Erdoğan administration – and of post-Ottoman Turkey in general – suggest that Ankara is actually pushing for more: it wants to impose its own agenda and perception over its allies.

More and more international observers wonder if Turkish leaders, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan in particular, are truly capable of implementing a change. There are some signs indicating this might be possible, although the more knowledgeable pundits remain sceptic, claiming that a return to the reformist agenda of the early years of the government’s mandate (2002-2009) is impossible.

Against the backdrop of a worsening economic crisis, Turkey is trying to reconnect with its former allies, after years of pushing them away with its aggresive rhetoric and policies. However, Ankara must also take into account its relationship with Russia, given that it is dependent on that country for energy, agricultural products, tourism and trade.

The discovery in recent years of significant deposits of natural gas in the Eastern Mediterranean area has triggered a competition with possible long-term ramifications, not just for countries that own the deposits in question, but also on the European Union’s strategic sovereignty.

Turkey’s diplomacy is non-conflictual, unlike that of Romania and Poland, the Kremlin’s loudspeaker, Sputnick, writes. The publication presents the Romania – Poland – Turkey Trilateral meeting in Bucharest from its own perspective and makes up non-existent fractures in the approaches of the three countries.

February 25 marked the first military operation ordered by president Joe Biden. US forces bombed targets in Syria used by Iran-led militias. The airstrike has brought back in the limelight a nearly forgotten war, recalling the complexity of this conflict with regional ramifications.