February 25 marked the first military operation ordered by president Joe Biden. US forces bombed targets in Syria used by Iran-led militias. The airstrike has brought back in the limelight a nearly forgotten war, recalling the complexity of this conflict with regional ramifications.

The US and Iran trade airstrikes carried out and targeting Iraqi militias

The Americans struck Syria, but their real targets were actually Kata’ib Hezbollah and Kata’ib Sayyid Shuhada, two Iraqi militias with known ties to Iran, standing accused of having orchestrated several recent airstrikes on American military bases in Iraq. It was not the first such attack for Kata’ib Hezbollah. This military group, which has been active ever since the war in Iraq, when it fought American forces, was behind the 2019 airstrikes on American military bases and was involved in the assault on the American embassy in Baghdad by Shiite protesters. Washington responded to the escalation of anti-US military operations with the assassination of Qassem Soleimani, the commander of the Quds Force of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps. Among other things, Soleimani was in charge of Shiite militias in the region. The airstrike also killed Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, the commander of Kata’ib Hezbollah. Their assassination has pushed Iran and the United States on the brink of war, yet hostilities stopped after a demonstrative attack to which the United States chose not to answer. Since then, the number of airstrikes targeting US military bases has gone down too, and this February’s airstrikes were meant to test the reaction of the Biden administration. Considering that the new American president has implied he is willing to resume dialogue with Teheran and even bring the United States back into the nuclear agreement (although not without a cost), it is very likely Iranian leaders wanted to see if the Americans truly want things to return to normal at any cost. Biden’s answer was clear: no. It must be said, however, the airstrikes had a limited impact, which suggests the US merely wanted to send a message, not burn all bridges in its relations with Iran. It remains to be seen whether things will stop here, given that a new airstrike hit an American military base on March 3.

Iraqi militias are not used just to test the Americans’ will. They play an important role in Iran’s regional policy, more particularly in Syria, where they’ve contributed, alongside Hezbollah and the Shiite militias from Afghanistan, to rescuing the Assad regime. Actually, Kata’ib Sayyid Shuhada seems to have been founded with the very purpose of fighting in Syria. The militia’s main objective is protecting Shiite holy sites, particularly the tomb of Zaynab, the granddaughter of the prophet Muhammad and Imam Hussein’s sister. When Iraqi militias were dispatched to Syria, the war that had gripped the country in the wake of the Arab Spring protests was no longer an internal matter, but a regional conflict, with much higher stakes than survival or removing the Assad regime.

A war ignited by a graffiti

The revolution in Tunisia broke out after Mohamed Bouazizi, a fruit peddler, set himself on fire in December, 2010. The spark that ignited the Syrian civil war more than two months later was a message spray-painted on a high-school wall in Der’a. The details are still blurry, some reports placing the event in early March, while others in mid-February, the message being a dry “it’s your turn, Doctor” (Bashar al-Assad is a medical professional, which is common knowledge among the Syrian people). According to different accounts, the message referred to the Syrian dictator by name. All sources, however, seem to agree on the events that followed: around 20 children studying there were picked up by Assad’s infamous secret service and taken to prison, where they were detained, beaten or even tortured for weeks. Their families, who knew nothing of the whereabouts of their children, demanded their release, giving rise to the first protests that quickly spread to other cities, fueling public unrest that had been building up over the years. Tension had been escalating also in the wake of extreme drought in mid 2000s, which forced tens of thousands of poor farmers to relocate to urban areas, in search of a better life.

When the uprising started, things only went from bad to worse. Fearing the liberating wave sweeping the Arab world would soon reach Syria (Tunisia’s Zine el Abidine ben Ali and Egypt’s Hosni Mubarak had already been removed from power), the regime answered with force. Thousands of protesters were arrested. Security forces opened fire on demonstrators, which did nothing but inflame them: every funeral was an excuse to stage a new rally. At one point, some of the security officers and soldiers preferred to defect, turning arms on the regime rather than firing on their own folk, so the revolution turned into a civil war.

Again, the situation deteriorated. To justify its acts of brutality, the Assad regime pretended to be fighting terrorist groups, just like the West. It released actual jihadists from prisons, to ensure a genuine terrorist presence on the ground. To make matters worse, al-Qaeda seized the opportunity of getting involved in a new civil war, and dispatched a fighting force against the Assad regime. A part of these militants, who had set up the al-Nusra Front, branched out of al-Qaeda and founded the Islamic State (ISIS), a military group so powerful that only an international coalition and significant manpower could defeat, both in Iraq and in Syria.

The disaster left behind by jihadists is just a small part of the tragedy in Syria. The fighting razed whole districts and cities to the ground. On numerous occasions, the regime used chemical weapons against the civilian population. Syrian and Russian air forces repeatedly bombed areas in the city, sometimes even hospitals. To survive, millions were forced out of their homes.

A broken country, at the mercy of foreign forces

The Syrian civil war seems to have reached a deadlock, and the continued involvement of foreign forces hinders any progress. The Government in Damascus continues to control most of the Syrian territory, spanning from the Mediterranean, alongside the Libyan and Israeli borders, to the borders with Jordan and Iraq, beyond which point its presence remains limited. Fighting for the Syrian regime are also Russian and Iranian combatants (many of them by proxy), and this is quite telling of just how much Assad is really in control. Not only does he need them if he is to survive, but even if he did manage to keep his country in check on his own, it is difficult to believe he will be able to tell them to leave.

Rebel forces (including a large number of Islamic combatants and jihadists) are trapped in the Idlib province, the last rebel-held stronghold in the north. With the help of his allies, Assad would most likely manage to defeat them (which is what the latest skirmishes of government forces seem to suggest), but Turkey will in no way allow it. Ankara wants Assad gone, and since the civil war started in Syria, it has been supporting rebel groups and deploying forces in the Idlib area. In early March, 2020, the Turkish army launched a massive offensive on Syrian forces, on the one hand to stop the Syrian onslaught against the rebels, and on the other hand as retaliation to a deadly airstrike on Turkish forces the previous month. At the same time, Turkey will also keep a close eye on the Syrian Kurdish YPG faction, which it doesn’t want anywhere near its borders. We should not overlook the fact it was Erdogan who deployed forces against the Kurds in October, 2019, forcing American forces to pull back from the area.

Washington never abandoned the Syrian Kurds, however, as it was accused in 2019, in autumn. YPG-controlled militias under its protection control northeastern Syria and a great part of the east as well. US military are stationed in the area, ready at all times to intervene if pro-Assad forces try to overstep their borders, which was the case of the battle of Khasham in February, 2018.

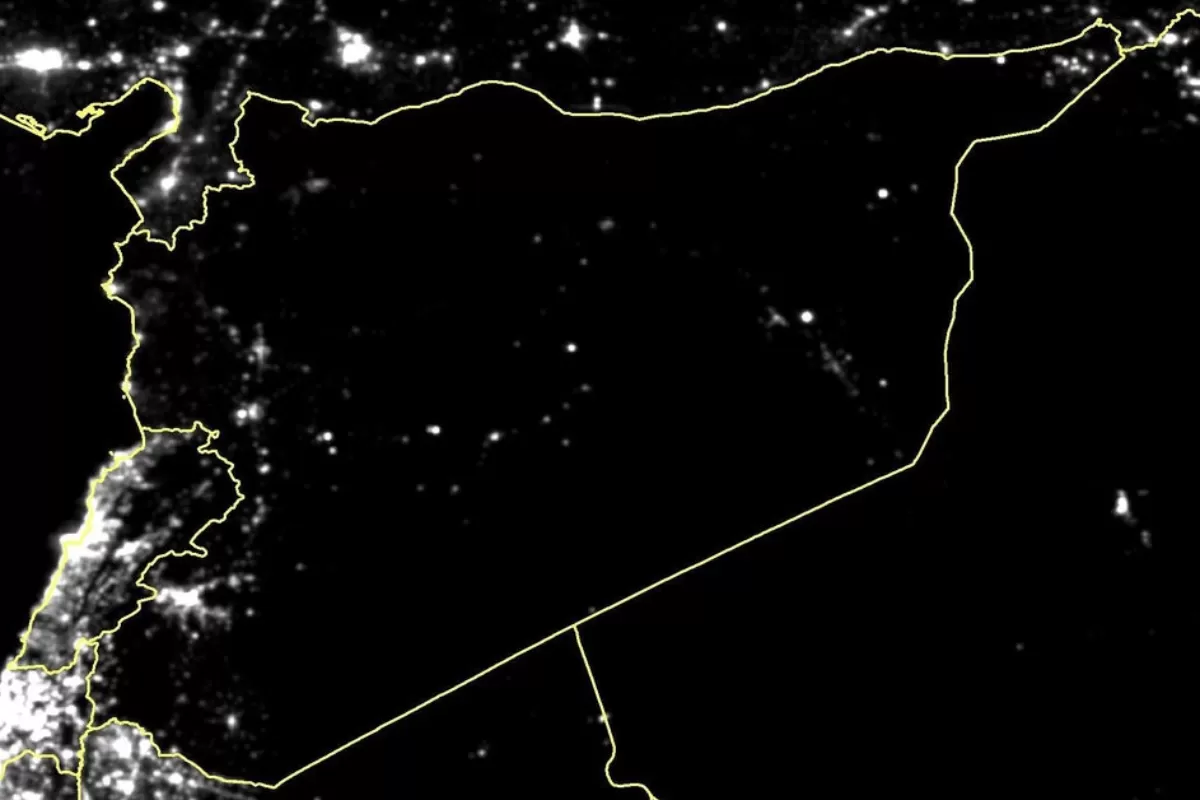

Syria sinking into darkness

Ten years after Assad’s security forces arrested a bunch of children for a graffiti, Syria is but a shadow of the country it once was. According to the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, 6.6 million Syrians were forced to flee the country and another 6 million people were internally displaced during the war. Tens of thousands of people disappeared without trace in the prisons controlled by the regime or the rebels. The country was destroyed to such extent, that even if they were willing to come home, refugees now have nothing to return to. Reconstructing the country would take hundreds of billions of dollars, money Syria doesn’t have and which it couldn’t raise from external sources. The war is frozen, but not over. The forces sent by other states, Shiite and Kurdish militias, Islamic rebels and jihadists, armies of various sizes and Assad’s own supporters are all standing by. Even in defeat, the Islamic State continues to stir trouble in the region – the Syrian Observer for Human Rights submits regular reports of ISIS attacks in the region.

As the latest US airstrike has revealed, Syria has now become the epicenter of clashes between third countries. Iran and Israel are now caught up deep in this conflict, the latter ordering regular airstrikes on installations Teheran is obstinately building. Of course, Israel never asks Bashsar al-Bassad for permission to enter Syrian air space.

While foreign combatants continue to flow into Syria, Syrian fighters become cannon fodder elsewhere: a few thousand Syrian military fought for Turkey in the recent Nagorno-Karabakh war, as well as in the conflict in Libya.

In March, 2015, the #WithSyria coalition, made up of 130 NGOs from all over the world (Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, Oxfam, Save the Children, etc.), released a series of satellite images showing Syria sinking into darkness: 83% of all lights visible at night over Syria prior to the war have gone out since March, 2011.

In 2021, darkness continues to rule over Syria.