Why have neither the weight of sanctions nor the scale of losses on the battlefield pushed the Kremlin toward compromise.

Bulgaria’s government stepped down after facing several protests over a two-weeks period. It was a surprise move in a country where disgraced politicians rarely back down, and even reformists that emerge from protest waves end up by doing politics “in the old ways”.

Behind the façade of resilience lies a system increasingly driven by asset seizures, political loyalty, and the enrichment of a new elite.

Bulgaria needs to find another owner for its Lukoil refinery after the US imposed sanctions on the Russian giant. There is a good chance that instead of attracting international investors, Sofia will turn to local barons.

Russia’s closest ally, Belarus, has been increasing its hybrid operations against its EU neighbors, directing migrants towards their borders and closing its eyes to increasingly brazen smuggling. The goal is to cause instability.

An ethnic Russian influencer in Estonia was arrested after he spread Moscow’s narratives for years. Oleg Besedin had financial connection both with Russia and with Estonian political parties supported by the country’s Russian community.

President Trump's peace plan, which was communicated more in terms of a "diktat," has little to do with Ukraine. In fact, in an attempt to save Putin and give Trumpism a fresh start, the strange American president seems willing to sacrifice Ukraine and, with it, European security.

An anti-corruption campaign targeting former high ranking Georgian officials may hide a drive by Georgia’s eminence grise, oligarch Bidzina Ivanishvili, to get rid of associates that have become too ambitious.

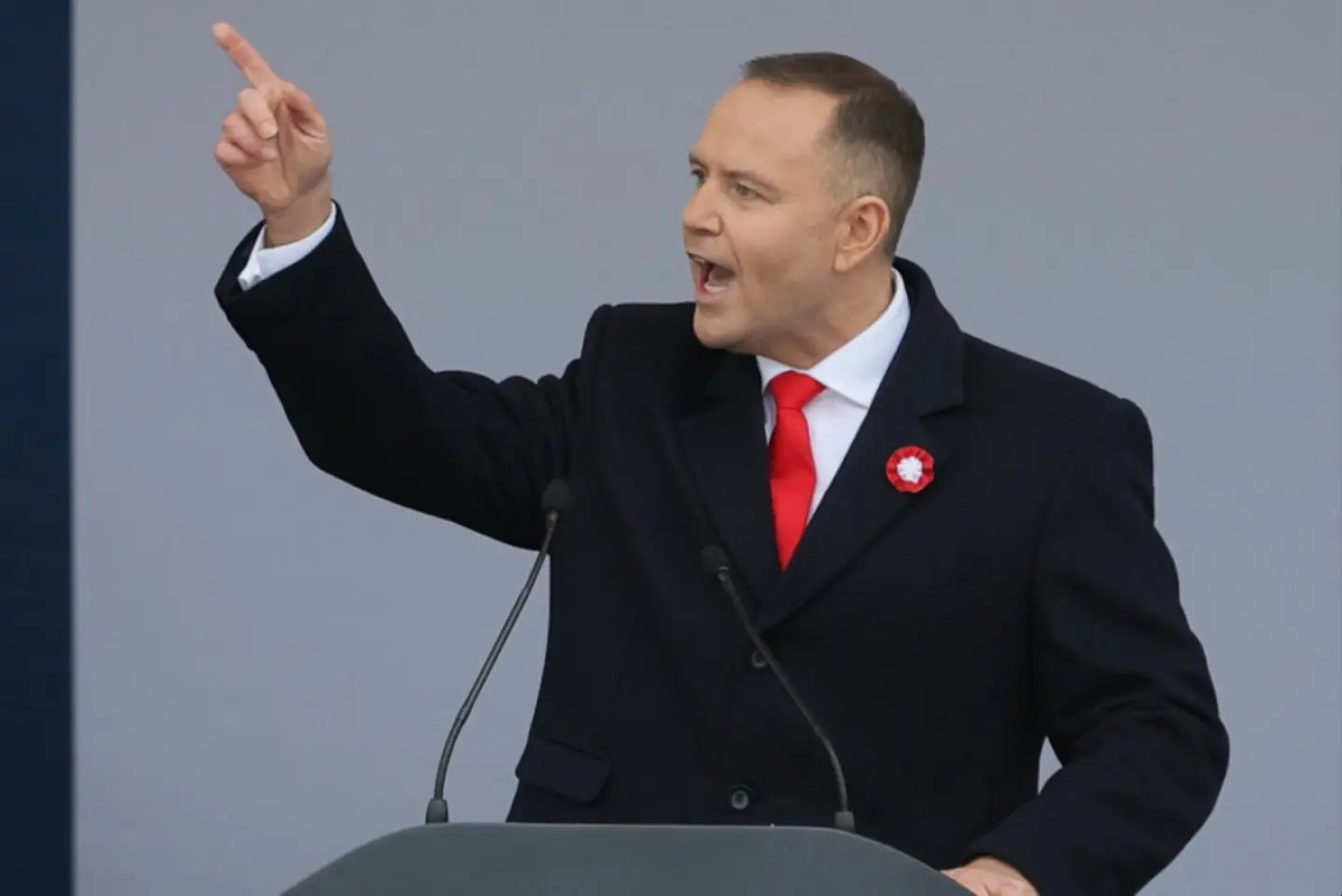

In his first hundred days in office, Poland’s new president has shown himself to be both a fighter and a tactician. Whether he is also a statesman remains to be seen.

Romanians are among the biggest consumers of information on social media in Europe and, at the same time, among the most vulnerable to disinformation campaigns targeting their users.

Polls show a society united around national defense, but one that seems increasingly ready for a generational change in politics.

A ceasefire would not simply return things to business as usual, as Russia’s wartime economic reorientation and the deep mistrust will complicate any post-war reset.

Bulgaria and German defence giant Rheinmetall have finalized an agreement to build a new arms production facility in Sopot, Central Bulgaria.

The resizing of the US military contingent deployed to Romania has triggered a wave of indignation and patriotic panic attacks among local pro-Russian propaganda outlets, generously peppered with disinformation and outlandish allegations.

Hundreds of Belarusian companies support Russia's war effort, supplying it with, among other things, shells, drones, chassis for military vehicles, and components imported from the West.

The parties that make up Estonia’s ruling coalition were crushed in the local elections by the party supported by the country’s Russian-speaking population. This may spell trouble – and a change in policy – for the parliamentary elections due in two years.

The EU is forcing us to eat insects, wants to replace Europeans with migrants, controls our internet, and manipulates our elections. These are some of the conspiracy theories targeting Brussels.

Erdoğan’s ally in Northern Cyprus has suffered a crushing defeat in the presidential election – a clear sign that Turkish Cypriots no longer support Ankara’s regional policies, at a time when those policies are also being challenged by the growing interest of the United States and other powers in the Eastern Mediterranean.

The budget sends a clear message – Russia is preparing to live, and fight, as a besieged fortress for years to come, even if doing so slowly drains the vitality of its economy and society.

A month after Russian drones were brought down over Poland, Warsaw feels normal again. Politicians resumed their quarrels, and the news cycle has moved on. Yet something in the public mood has shifted – a low, persistent awareness that Poland is being watched, probed, and measured.

Adam Michnik's creed has always been to serve the values of liberalism and pluralism, where reason guides society, to serve basic Christian values, where truth will set us free and where there is morality in politics; and that can only happen in the world of European civilization.

Ukraine faces increasing dependence on Western support. Russia will likely face critical fiscal constraints within 12-24 months. Meanwhile, China, the United States, and some third countries are extracting gains from the conflict.

The ruling Georgian Dream party won, by a landslide, yet another round of elections in Georgia. The elections took place against a background of democracy backsliding, and increasing harassing of a fractured opposition.

(Pro-)Russian propaganda seeks to convince the world that Russia is unstoppable. However, the parliamentary election in Moldova showed that, when facing smart opposition, Moscow cannot win the hybrid war — not even against a country with infinitely smaller resources. The lessons Moldova offers may prove valuable for both NATO and Romania.

Georgia’s leaders mimicked Donald Trump’s rhetoric hoping to reset the relationship with the US, which was damaged due to Tbilisi’s democratic backsliding. However, Washington didn’t buy it.

The pro-Europeans achieve a landslide victory in the parliamentary election in Moldova, following an election dominated by geopolitics and Russian interference, whose efforts ultimately proved futile. However, the results also show that the Republic of Moldova continues to remain deeply divided.

Expert: “I slept through the news about Russian MiG-31s flying over Estonian territory. That says something. If you had other things to do, it means this incident wasn’t that important”

The campaign of arrests and court cases targeting Turkey's main opposition parties underscores the country's slide toward authoritarianism, a trend that has become increasingly clear over the past decade.

Newly leaked internal documents, made public after the exposure of Russian activists’ data, once again reveal the scale of financial flows directed at promoting pro-Russian ideas – in this case, in Moldova. The leaked documents highlight the key channels of financing, the structure of spending, and their potential Russian influence on public opinion abroad.

The European approach based on rules, deliberation and consensus seems ineffective in a world affected by multiple crises, with numerous actors refusing to play by the book. It is a world in which Brussels must (re)gain its relevance.

After the collapse of communist regimes in the early 1990s, the nations of Central and Eastern Europe faced a pivotal choice: embrace Western-style democracy and market economics, or remain in the post-Soviet sphere. Today, more than three decades on, the results of that choice are stark.

On Tuesday night, Poland’s airspace came under pressure from Russian drones in what experts call the most serious incident since the start of the war in Ukraine. The military responded, the government convened emergency meetings, and allies expressed support—but the question remains: what will the West do next?