Bulgarians are about to vote for the fifth time in two years, and polls suggest that the political stalemate is likely to continue after the elections. Seemingly out of fresh ideas, the political parties are divided along the same lines, liberals against conservatives, pro-Russian vs. pro-European, newcomers vs. the old guard of allegedly corrupt politicians.

One book and a documentary film claiming that Pope John Paul II knew about and covered sexual abuses against children lead to a huge scandal in his native Poland, where the former Pontiff is revered. Conservatives and the far-right scrambled to "defend the good name" of John Paul II and seem poised to use the scandal to their advantage in the upcoming elections.

Prime Minister Viktor Orban finds himself in a complicated situation. Politically, he gets increasingly isolated from its Western partners. Hungary's economy is in crisis, and the European funds that could relaunch it have been blocked due to anti-democratic slippages. With all the friendship that Budapest has shown to Russia, there isn’t much Russia can do to help, being itself increasingly affected by Western sanctions. Orban's solution appears to be to block Finland and Sweden's entry into NATO until the EU unlocks funds for Hungary. However, this blackmail policy may have reached its limits.

From disinformation spread by propaganda regarding the imminence of a war in Transnistria, Russia has now moved to official statements about Ukraine’s plans to invade the separatist region of the Republic of Moldova. Transnistria seems to be used to draw attention away from Russia’s plan to destabilize Moldova, as well as from the defeats sustained in Ukraine. Besides, the pro-Russian opposition in Chișinău could take advantage of the panic induced by the prospect of war.

The first anniversary of the full-scale invasion of Russia provoked a wave of pro-Ukraine marches in Bulgaria, a country traditionally associated with heavy political dependencies from Russia. The pro-Russians stayed mostly out of sight for the one year anniversary of the war, but that does not mean that they went everywhere: Moscow still has its supporters in Bulgaria, both among the politicians and the public.

Putin expected Ukraine to give in quickly, and the West, frightened by the prospect of a gas crisis, divided and unable to make firm decisions, would react rather rhetorically, as it happened with the war in Georgia in 2008, or the initial attack on Ukraine, in 2014. Ukraine resisted, dispelling, at the same time, the myth of the mighty Russian army, and now it only envisions victory. Both camps seem determined to fight until they achieve their goals. The war continues.

Poland positioned itself as one of Ukraine’s main supporters: it allowed its territory to be used for arms deliveries while becoming a major arms supplier in its own right and convinced its NATO allies to support Ukraine even more. In parallel, Warsaw is engaged in a process of strengthening its own army. All this shows that Poland is turning into a key actor for the European security, an actor that is, however, increasingly exposed to the theses of Russian propaganda.

The timespan of the conflict, which exceeded original estimates, the losses sustained so far and daily hardships continue to leave their mark, and many Ukrainians now struggle with war fatigue – even though they are still determined to resist. Russian propaganda has been trying, using its specific mechanisms, to capitalize on this fatigue and on any other problems that are inherent to such a destructive war that seems to be never-ending.

The power shift has so far unfolded without any major incident or scandal, and the key protagonists – the outgoing Prime Minister, Natalia Gavrilița, the Prime Minister designate, Dorin Recean, and president Maia Sandu – said that the change of administration occurs against the backdrop of growing security tensions. There are however signs that the true reasons behind the Cabinet swap have to do with the slow pace of reforms and ruling-party infighting.

Nearly one year after the onset of the Russian invasion in Ukraine, Bulgaria is still undecided on how to integrate the Ukrainian refugees. Activists, however, strive on. Most Ukrainians move on.

Hungary has a “preferential” contract for its gas imports from Russia, but has now ended up paying more than other European states. Prices for fuel and Diesel have skyrocketed, and inflation has hit the highest mark at EU level. Besides, Budapest’s bypassing European regulations and values has prompted the European Commission to freeze €7 billion worth of EU funds to Hungary. All that spirals into an economic crisis generated, for its most part, by Viktor Orbán’s policies.

The Czech presidency seems poised for a major shakeup, as retired general Petr Pavel is preparing to take the office from Miloš Zeman. Unlike his predecessor, a pro-Russian and pro-Chinese politician with a knack for challenging the country’s Constitution and governments, Pavel is staunchly pro-Western and he vowed to cooperate with the equally pro-Western government. The president-elect also expressed his support for Ukraine, and caused a (for now) minor row with China.

The letter Z, written in paint on Russian tanks, a mural of “Holy Javelin” on a block in Kyiv, “babushka Z” coming out to meet the Russian army or the insult “Idi nahui” addressed to the invading forces – these are some of the symbols associated with the war in Ukraine. Moscow uses symbols to justify its invasion and convince Russian men to enlist; Ukraine, to raise the morale and determination to resist, but also to strengthen the population’s feeling of national identity.

As Russia launched a massive attack on Ukraine in early 2022, millions of civilians fled the country and went West, out of harm’s way. Many chose to stay in Poland. They received some help from the state, but they mostly benefited from a network of volunteers providing everything from daily necessities to accommodation and jobs. Eleven months on, as some Poles are getting increasingly weary of refugees, the latter are still trying to adapt while dealing with the war traumas.

The Russian bombardments on Ukraine also alerted the authorities in Chisinau after, on several occasions, fragments of rockets fell on the territory of the Republic of Moldova. The incidents showed how vulnerable the Republic of Moldova is from a military point of view, without an anti-aircraft defense and with an army of only six thousand people. But the biggest danger to the security and stability of the state seems to come from elsewhere – from the informational space controlled by Russia and from some politicians who enjoy, openly or secretly, the support of Moscow.

The coalition led by Benjamin Netanyahu depends on ultra-nationalist and religious parties, which will wield unprecedented power. Netanyahu finds himself caught between the radical agenda of these parties and the need to strengthen cooperation with the United States and Arab countries - sensitive, at least declaratively, to the interests of the Palestinians - to undermine Iran's nuclear program.

In mid-January, the Russian Defense Ministry for the first time gave credit to the Wagner Group for its exploits in Ukraine. Tensions between the conventional army and the Wagner Group, whose founder criticized the war tactics of Russian generals, are common knowledge. Besides, in recent years, the Kremlin preferred to keep its dealings with the Wagner Group and its activity far from prying eyes. Recognizing the merits of this military contractor, whose very existence is illegal even in the eyes of Russian legislation, confirms the Wagner Group’s growing contribution to the war effort.

Poland ranks sixth in Europe regarding cyber threats. The targets are not only private firms and Internet users, but increasingly hospitals, transport companies, banks and all administration branches. Authorities warn that the number of attacks is increasing and allege that Russia is behind them, as it tries to destabilise Poland for the key role it plays in supporting Ukraine.

Classical disinformation themes and fake news were increasingly replaced with war propaganda as an instrument of publicizing Moscow’s false narratives. The purpose of these narratives, irrespective of how they were presented to audiences, was to manipulate public opinion, to legitimize Russia’s actions, to conceal war crimes and atrocities committed in Ukrainian settlements, to shatter the Ukrainians’ morale and fighting spirit, as well as to spread a controlled form of chaos in the proximity of ex-Soviet space.

Since the beginning of the war in Ukraine, more than 5 million Ukrainians have crossed the Romanian border, fleeing the war. Most chose to go further west, but some decided to stay here. Officially there are 90 348 of them, but the real number could be much higher. Before arriving in Romania, many only knew what Soviet and Russian propaganda had told them, so they were amazed at what they found and how they were received. With all the help they get, however, there are problems, as the refugees find it difficult to integrate due to language barriers and many still feel the psychological impact of the drama they have been through.

As Czech presidential elections are nearing, populist parties are trying to gain support from pro-Russians by exploiting the issue of Ukrainian war refugees. Most Czechs continue to view refugees positively, but a growing minority believe they are a burden.

Rusia a avut mereu oamenii săi printre reprezentanții clasei politice și administrației de la Chișinău. Unii nici nu au încercat să-și ascundă relația cu Moscova, alții par să-și fi jucat foarte bine rolul, plasându-se în fruntea unor mișcări naționale și proeuropene, ceea ce, probabil, i-a permis Rusiei să controleze anumite procese politice din interior. Veridica îi amintește, în acest al doilea episod, pe cei care au menținut Republica Moldova în siajul Moscovei pentru o bună parte din ultimele două decenii.

The Chinese authorities have relaxed anti-pandemic measures after a wave of protests over the zero-Covid policy. It is a rare concession from a regime that in recent years has tightened its grip on society and has not hesitated to use its repressive apparatus against the pro-democracy movement in Hong Kong or the Uyghurs in Xinjiang. However, the step back seems to be a tactical one and there are no signs that it could be followed by a political relaxation.

The Government in the Republic of Moldova has been accused of having given in, once again, to the blackmail of Russia and Transnistria when it accepted to deliver all Russian gas imports to Tiraspol in exchange for electricity. As a matter of fact, for the time being Chișinău authorities don’t have too many alternatives at their disposal in terms of electricity and natural gas supplies, and any projects already launched with a view to diversifying Moldova’s energy sources need time to be implemented.

Russia has always had people defending its interests at the level of the political class and administration in Chișinău. Neither of them have tried to hide their connections to Moscow, while others seem to have played their part flawlessly, ending up at the helm of nationalist and pro-European movements, which most likely allowed Russia to control certain political mechanisms inside Moldova. In this first instalment, Veridica offers an overview of major politicians who have left their mark on 1990s’ Moldova.

As pro-Europeans in Sofia are confident that Bulgaria will switch to the Euro in 2024 pro-Russian parties claim the adoption of the EU single currency will only bring economic instability. Debates and heated exchanges on this topic might become part of the political landscape in the next two years. Disinformation is bound to be part of the picture.

Russia’s war in Ukraine has displaced a huge number of Ukrainian refugees. Millions of people fled Ukraine, heading to other European countries, although many chose to relocate to some of the country’s safer areas. Russia has been trying to turn this crisis to its advantage. In EU countries, it has been promoting false narratives designed to generate public hostility towards Ukrainian refugees. In the case of Ukrainians relocated at national level, Russian propaganda sought to focus on fueling public unrest and internal tensions.

The last round of peace negotiations between Russia and Ukraine as part of the war launched by Moscow took place in March and did not produce any results. For over eight months, the negotiation process is in a deadlock, neither party being willing to accept peace at any cost: both Kyiv and Moscow want victory.

The latest developments in Chisinau suggest that the Republic of Moldova seems to have become the target of a hybrid war launched by the Russian Federation to topple the current pro-European power and bring that state back into Moscow's sphere of influence. The authorities in Chisinau are forced to face an unprecedented energy crisis, successive increases in the prices of the most important products and services, but also protests organized by parties believed to be backed by the secret services in Moscow. Adding to these challenges is the deepening security crisis as a result of the war in Ukraine, particularly the missile and drone attacks on Ukrainian energy infrastructure in recent weeks.

Poland's conservative government is increasingly critical to Germany, by virtue of a "historical" conflict that is largely imaginary. Anti-German sentiments are sometimes mixed with anti-EU ones, and even Russia, Poland's traditional enemy, is viewed more leniently. Could this be a first sign that a Polexit is being prepared?

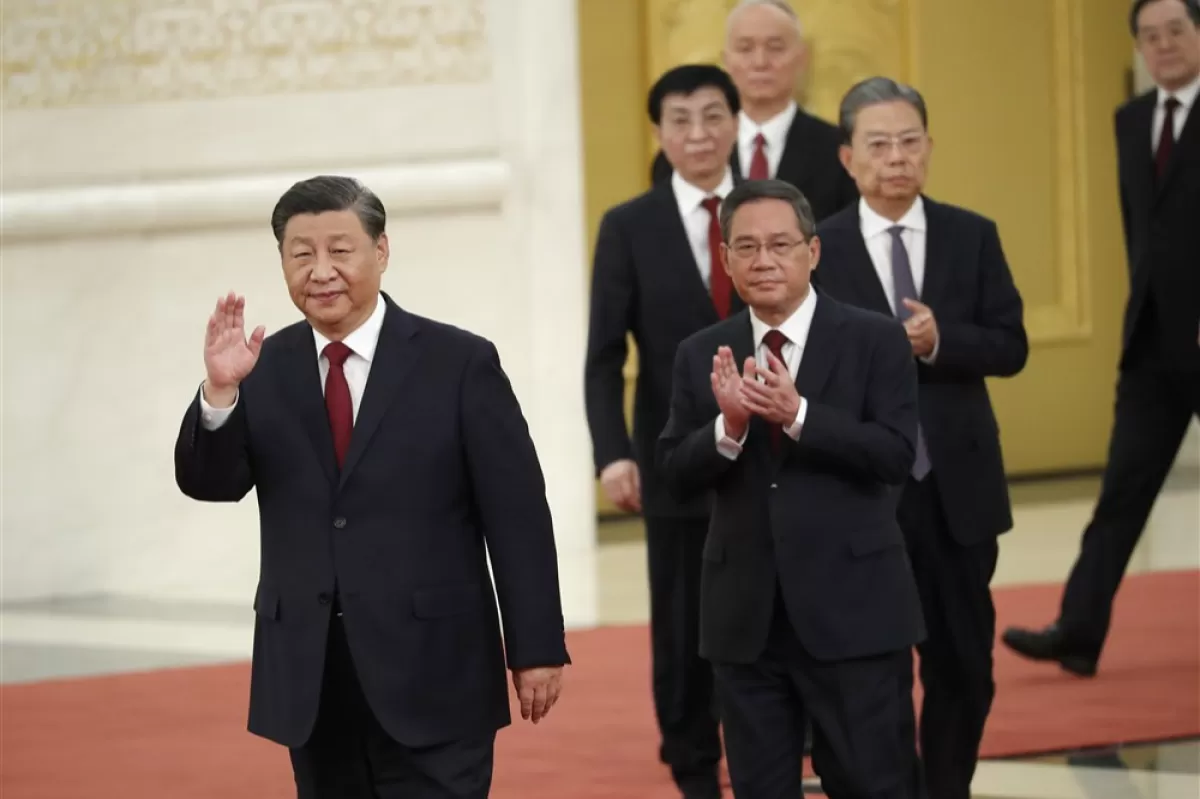

The 20th Congress of the Chinese Communist Party has tightened Xi Jinping’s grip on power in China. Before him, only the founder of the People’s Republic of China, Mao Zedung, had enjoyed such sweeping control over the country. The Xi era will likely go down in history as one of the most repressive regimes at home and most aggressive overseas, compared to the previous three decades of relative liberalization.

For almost ten years the Prague Castle, the seat of Czech presidents, was one of the most pro-Russian and pro-Chinese places in the European Union. Miloš Zeman will leave office on March 8. It is too early to say who will succeed him, but we can already certainly say that the style and content of the presidency will change fundamentally.