The 20th Congress of the Chinese Communist Party has tightened Xi Jinping’s grip on power in China. Before him, only the founder of the People’s Republic of China, Mao Zedung, had enjoyed such sweeping control over the country. The Xi era will likely go down in history as one of the most repressive regimes at home and most aggressive overseas, compared to the previous three decades of relative liberalization.

After securing his third mandate, Xi has truly become the sole leader of China

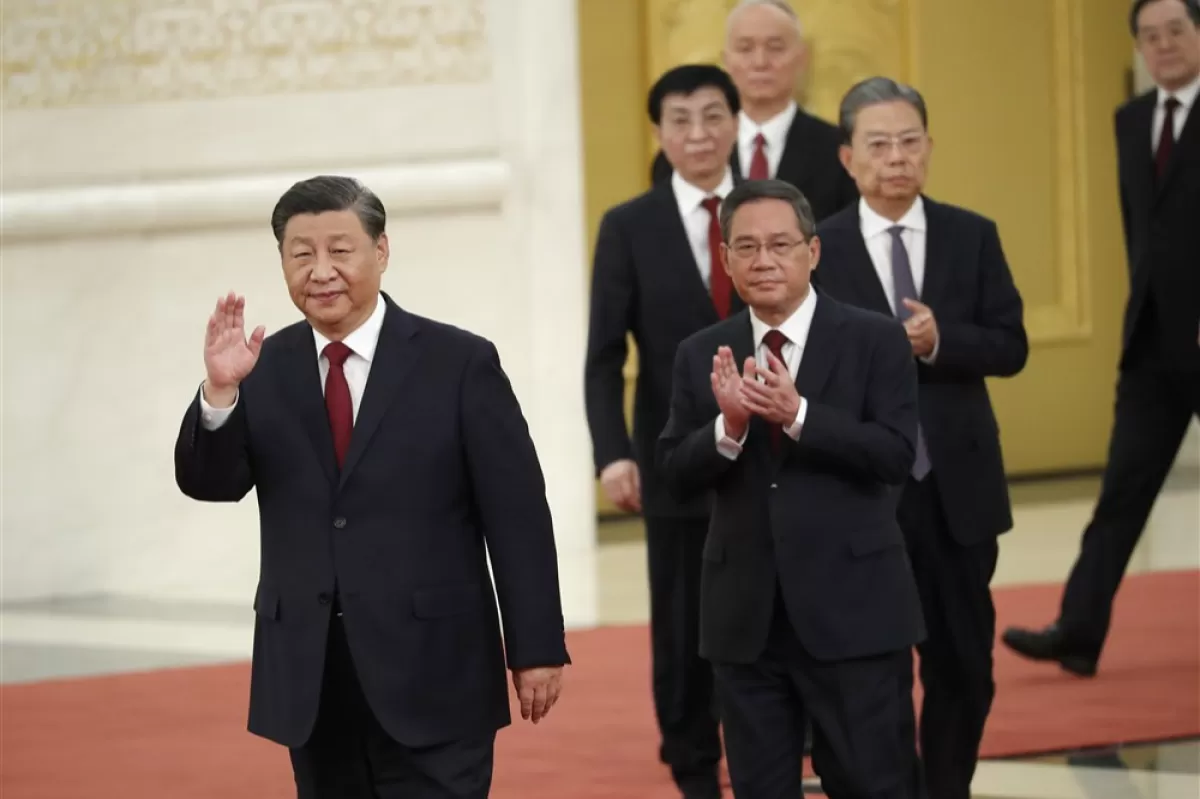

The 20th Congress of the Chinese Communist Party has cleared up all doubts as to who is the one and true leader of China: Xi Jinping. Just like the “Chinese dripping machine”, Xi Jinping gradually got rid of all his rivals, and I believe the incident at last month’s party congress, when former president Hu Jinato was forcefully led out of the Great Hall, is symbolic of the “Xi era”, which started with his reelection at the helm of the party, and will most likely end with him securing a new term as head of state in March.

The Chinese Politburo, the Permanent Committee of the Party’s Political Bureau, now comprises seven people, all loyal to Xi and each vetted over the course of the first two mandates.

What happened in Beijing in late October is part of the cycle of Chinese politics. Every five years, the Chinese Communist Party, the ruling party in China, organizes a Congress in a huge building with the Red Star towering on top and a few thousand people in attendance. The Congress is a mix of several events. It is in part a sort of “state of the union” voiced by Chinese leaders who expose their own perspectives on the latest developments in China in recent years as well as future lines of action. This is also the time when Communist Party members stage rallies on key topics that the party leader presents in Congress. And, last but not least, comes the “coronation” of the new leader, which many might find shocking considering the troubled times we live in. In a nutshell, such is the transition of power in China. Starting 2012, the position has been held by Xi Jinping. It came as no surprise when his name was announced as General Secretary of the Party, reelected for the third consecutive mandate, an unprecedented move since the Mao era. Xi had methodically paved the way for this break from Deng Xiaoping’s limitations.

Then, the Congress announced the names of the Politburo members. Apparently an unrelated event, prior to the announcement, former president Hu Jintao was escorted out. The official story presented by state-run Chinese news agencies was that Jintao “was unwell”, while unofficial sources claim he and his close associates were the targets of a political purge by Xi due to their opposition. Two of these people, let’s call them viable contenders for the party leader position, were excluded from the Chinese Politburo. The announcement of the new Politburo structure followed shortly after Hu Jintao was removed by security from the Congress auditorium. Wang Yang and Li Keqiang, two moderate and respected leaders, were removed from the inner circle of power and replaced with two politruks loyal to Xi. Neither of them have displayed any opposition to the party in the last ten years. Yang, for instance, for all his experience, party seniority and, considering that China has been focusing on the most important provinces in economic terms, was expected to stay at the heart of Chinese political elites, but that was not the case. To the external observer, Xi’s radical choice gives an idea of where China is headed from now on. Li Keqiang’s place was taken by Li Qiang, a name that was virtually unknown prior to the congress. Qiang is the one who “managed” with an iron first the total lockdown in Shanghai, yet this is not what recommended him for a spot in the Politburo, but rather his friendship with Xi Jinping, spanning over two decades. When the current president was the party secretary for the Zhejiang province, Li Qiang became the provincial party secretary, and remained Xi’s right hand from 2004 to 2007, when he moved to Shanghai for a position higher up the political ladder. When Xi became president of China, he appointed his old friend governor of Zhejiang, and later on provincial party secretary of the Jiangsu province, grooming him for higher office. By 2017, Li Qiang was already part of the Chinese political elite. Following the legislative session in March, Qiang is expected to be appointed the new Prime Minister of China.

It will all come full circle in March, when the National People’s Congress will reelect Xi as president of China, who in turn will put his right-hand man at the helm of the government.

China – dialing up internal repression and external aggression

During his 10-year tenure, Xi has not just forced out his rivals, but he also built a system that virtually snuffs out any form of opposition towards the regime and his own office. He did so via institutions which, as recently revealed, have been quietly operating out of certain EU and NATO states. I’m referring to the 54 overseas police stations that report directly to Beijing. The revelation was made by Safeguard Defenders, a human rights NGO from Asia, headquartered in Spain.

These police-run stations were officially tasked with administrative activities addressing Chinese nationals abroad, but in fact “persuaded” some 300 thousand Chinese to return to China using various tools at their disposal. A recent report of Safeguard Defenders shows that these illegal commissariats are in fact spying on Chinese refugees in the West, intimidating them in order to keep them quiet. Countries such as Spain or the Netherlands have taken the NGO’s report very seriously. Ireland has even recently closed one such center that was functioning illegally on its territory. And this is most likely the tip of China’s spear of repression, particularly outside China, in the free world. It’s shameful that such a network can still exist right under the nose of democratic leaders.

Yet, beyond this activity in democratic countries, the Chinese Communist Party’s greatest struggle with the rest of the world is transparent in Taiwan.

The fact that Xi Jinping wants to capture the island is no secret. Neither is the fact that, in the last four years, the Chinese leader seized every opportunity to threaten the use of force, the same threat China is flaunting as the war in Ukraine rages on. “Crowned” for the third time, Xi Jinping naturally becomes a sort of second father to the nation. Taiwan, relations with Russia and the return to a centralized economy, will mostly likely underlie Xi’s term in office. As I previously wrote for Veridica, Mao Zedong had three goals: to end the civil war that destroyed China in the run-up to the establishment of communist power, to end foreign intrusions into Chinese territory, and to create a new, egalitarian society. Just imagine, Maoism prevailed despite severe economic difficulties. Xi Jinping is leading a country that is currently the world’s second economic power, and that makes me believe his power will exceed that of Mao, the man Xi always wanted to match in terms of achievements.

I noticed how Xi Jinping did not congratulate Vladimir Putin on his birthday. When he turned 70, the Kremlin leader did not get a nice pat on the back from the man who, prior to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, said they were tied by unlimited friendship. Xi Jinping didn’t even attend the dinner marking the end of the ‘Asian OSCE’ Summit in Astana. However, he did convey a message celebrating 65 years since the Beijing-Moscow Friendship Association was established. “The friendship between China and Russia has broad prospects and there are still great things to be achieved”, the Chinese president wrote in his brief message. It wouldn’t say much about his intentions, were it not for Jinping’s invitation extended to Putin upon their meeting in Uzbekistan in September, the first since the invasion.

“Faced with the great changes of our time at the global level, never seen before in all of history, we are willing with our Russian colleagues to serve as an example as responsible world powers and play a leadership role to steer that rapidly changing world onto a stable and positive development trajectory,” Xi said.

I don’t believe there are any fissures in China-Russia ties. Prior to Xi Jinping’s reelection, China played its cards closer to the chest. Regarding Taiwan, I think it’s only a matter of time before Beijing decides how to best deal with this “problem”, as Xi Jinping always points out. The Chinese leader will not refrain from using force to achieve what he has termed the reunification of China. In a nutshell, China in the “Xi era” will be more oppressive at home and more aggressive abroad.