Once a symbol of modernization and global integration, Russia’s digital sphere is undergoing a profound transformation under the pressures of war. The networks, platforms, and services that once promised convenience and openness are now increasingly shaped by state control, geopolitical isolation, and the exodus of skilled talent.

For decades, one of Russia’s undisputed advantages was its human capital—particularly in mathematics, engineering, and information technology. Rooted in Soviet-era scientific schools, Russian IT specialists earned global recognition for their skills and adaptability. In the post-Soviet decades, this talent pool helped build pockets of advanced digital infrastructure that rivaled, and in some cases surpassed, those of many European capitals. Moscow, in particular, became a “digital oasis,” where services ranging from e-government portals to cashless payments worked seamlessly, painting an image of a country confidently stepping into the 21st century.

However, these “pockets” never expanded at national level. Outside major cities, Russia’s digital landscape was uneven, often lagging behind even average European standards. While metropolises operated in one of the best urban digital ecosystems of the 21st century, much of the rest of the country still struggled with infrastructure that seemed stuck in the late 20th.

A New Digital Daily Life Under Militarization

The war in Ukraine has reshaped this landscape in profound ways. The “new normal” of militarized life has altered the everyday digital routines of millions of Russians. Foreign messaging platforms have been gradually pushed out, replaced by domestic alternatives—most notably Max, a state-controlled messenger whose data privacy and independence are widely questioned.

Government digital services, once celebrated for streamlining bureaucratic processes, now serve as tools of surveillance and enforcement. A few clicks are enough to restrict a citizen’s ability to leave the country or sell property. In the banking sector, increased integration of services with state systems—especially with the planned introduction of the digital ruble—gives authorities real-time insight into personal finances and the ability to impose fines instantly.

Urban residents, who once viewed digitalization as an unqualified blessing, are also experiencing its vulnerabilities. Drone attacks on Russian cities have led to temporary mobile internet shutdowns, instantly disrupting essential services—from mobile communications to contactless payments. Such disruptions occur without warning, complicating both daily life and business travel. Transport hubs like airports can be locked down for extended periods, making it difficult to plan even short trips.

The War, the Economy, and the IT Brain Drain

When the war began, Russia’s digital economy—its specialists, companies, and infrastructure—suddenly found itself at the center of attention. The country’s dependence on highly skilled IT workers collided with a wave of emigration, as thousands of professionals left to avoid mobilization or to seek greater personal and professional security abroad.

This exodus posed a serious dilemma for the Kremlin. On one hand, officials wanted to project strength by dismissing these departures or framing them as acts of disloyalty. On the other, replacing these specialists domestically proved nearly impossible. Many could easily find remote work abroad, maintaining their careers while severing physical ties with Russia.

Pragmatism eventually won out—at least partially. The government stopped short of officially labeling IT expatriates as “traitors” and refrained from imposing punitive tax hikes on those working remotely for Russian companies from abroad. This decision reflected the recognition that, without these professionals, critical sectors of the economy could falter. While pro-war hardliners called for harsher measures, the authorities have so far prioritized keeping the digital economy operational over ideological purity.

Russian Tech Business: Between Two Worlds

Over the past 30 years, Russia’s IT sector built not just domestic success stories but globally competitive products: popular messengers, antivirus software, high-performance banking services. While Russia never achieved self-sufficiency in hardware—relying heavily on foreign microchips and components—its software innovation was enough to make some companies global players.

The war, however, has forced an impossible choice. For many tech firms, “sitting on two chairs”—operating both in Russia and in Western markets—is no longer viable. Some, like the Belarusian gaming giant Wargaming, split their operations into separate Russian and international branches. But such arrangements carry risks: Wargaming’s Russian operations were soon stripped from their original owners in the broader wave of wartime asset seizures.

The very fact of being a Russian company has become a liability. Kaspersky Lab, once one of the most trusted antivirus providers globally, is now treated in much of the West as a potential security threat—mirroring earlier suspicion toward Chinese tech products. Similar concerns surround Pavel Durov’s Telegram, with debates intensifying over its cooperation with governments and prompting some users to switch to supposedly more secure alternatives. In some countries, Telegram’s operations face restrictions outright.

As a result, Russian tech giants face a stark strategic choice: remain in Russia and accept a shrinking, isolated market, or adapt to international demands at the cost of severing—or heavily reducing—ties to their home base.

The State’s Expanding Digital Grip

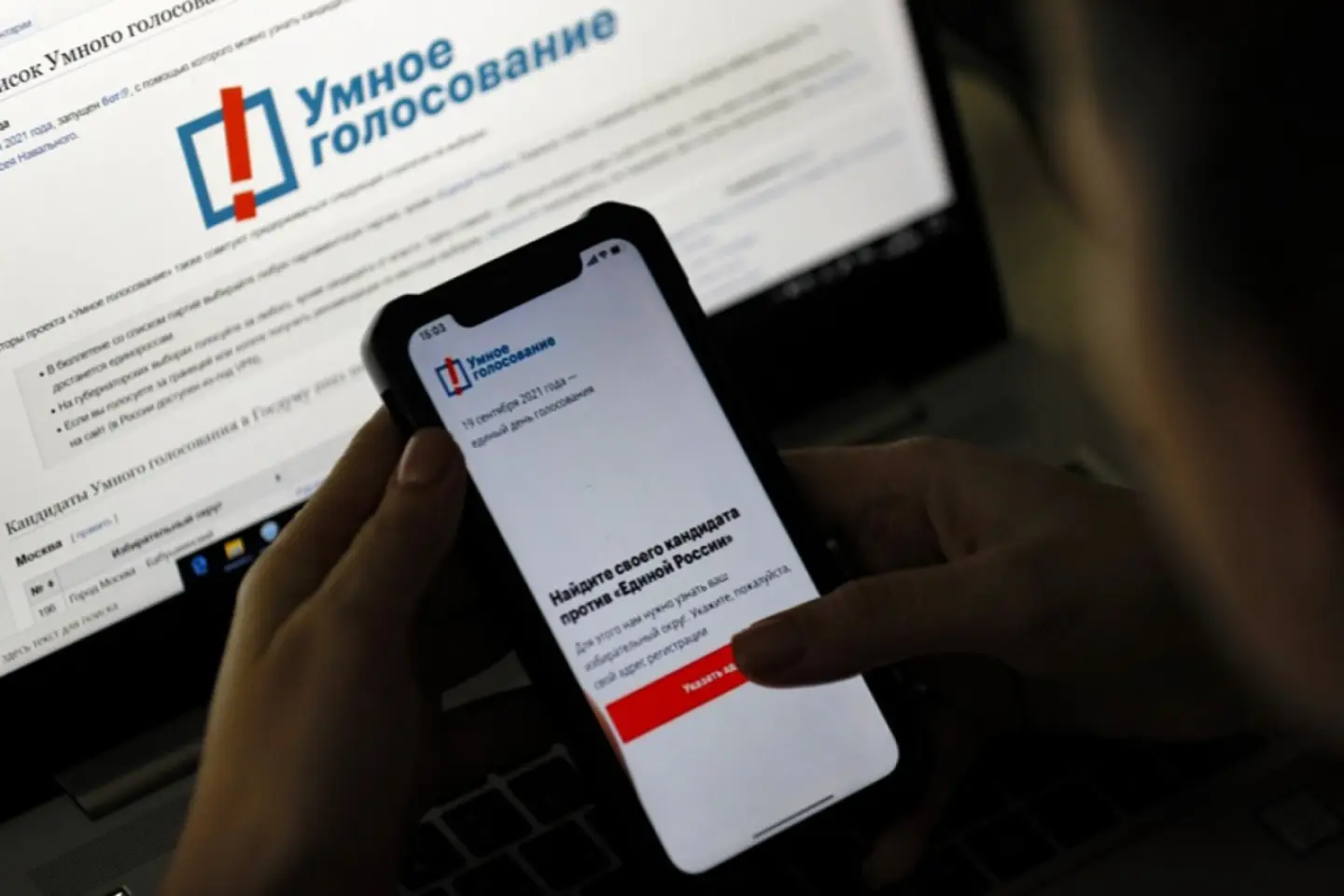

Following China’s example, Russia has begun to explore the full potential of digitalization as a tool of social control. While the scope and sophistication of Chinese surveillance remain unmatched, Russia’s trajectory is unmistakable. The pandemic offered the first mass test of integrating digital tools into state monitoring. The war has taken this further, embedding digital oversight into everyday governance.

What were once convenient, user-centered services aimed at reducing bureaucracy have become levers of state control. In the new system, the same e-government platforms that once empowered citizens now constrain their freedoms. Travel restrictions, asset freezes, and punitive fines can be executed seamlessly, with minimal due process and no physical interaction.

This evolution raises deeper philosophical and political questions—both within Russia and for the world at large. Where is the line between a digitally empowered society and a digitally monitored one? Can the benefits of widespread digitalization be separated from its potential for authoritarian abuse? Russia’s wartime experience offers a stark case study in how quickly a technology designed for convenience can be repurposed into an instrument of coercion.

From Digital Pride to Digital Paradox

The transformation of Russia’s digital ecosystem over the past few years is a story of paradoxes. The very infrastructure that once symbolized modernization and global integration now serves as a mechanism of isolation and control. The skilled professionals who built this system are increasingly absent from the country, yet remain essential to its functioning. Businesses that once thrived on global competitiveness now face existential threats from the very origins of their success.

For Russia, the question is no longer how to expand digitalization, but how to reconcile its two contradictory roles: as a driver of economic progress and as a tool of state power. The answer will shape not only the country’s technological future but also the nature of its society in the years to come.