When Karol Nawrocki stepped into the marbled halls of the Presidential Palace on Krakowskie Przedmieście on August 6th, few in Warsaw’s political salons expected him to fill them so noisily. A former head of the Institute of National Remembrance (IPN) and director of the Museum of the Second World War in Gdańsk, the 42-year-old historian from Poland’s Baltic coast arrived in politics as a newcomer with a pugilist’s swagger. His rise from an obscure cultural bureaucrat to the presidency was a gamble even by Jarosław Kaczyński’s audacious standards.

That gamble paid off – barely. Nawrocki’s victory over the opposition candidate Rafał Trzaskowski was narrow (50.89% to 49.11%), but enough to preserve for the Polish right its most important institutional fortress after losing power to Donald Tusk’s centrist coalition two years earlier. For the Law and Justice party (PiS), keeping the presidency was meant to secure a veto over the liberal government’s reforms. For Kaczyński, it was a chance to shape his own succession. Yet, after a mere hundred days, it is the protégé rather than the patriarch who seems to have seized the initiative.

From apparatchik to alpha

Nawrocki’s first months have been a study in political acceleration. He has shed the timidity of a first-time officeholder with astonishing speed. His aides say that, in terms of politics, he learned politics, “he learned in a hundred days what others take a decade to grasp.” Opinion polls confirm a striking honeymoon: according to the IBRiS survey for Rzeczpospolita, 55.8% of Poles rate his first hundred days positively, against 30.8% negatively. The figure conceals deep partisan asymmetry – nearly all PiS and far-right Confederation voters approve, but so do a modest 12% of government supporters.

Nonetheless, in a country where political alignments are tribal, even such cross-party appeal is rare. It reflects Karol Nawrocki’s unusual biography: neither a career politician nor a party functionary, he blends conservative values with a street-fighter’s authenticity. His friends recall his years in Gdańsk’s football terraces; his detractors point to the same past to portray him as a “hools president.” His public persona – half scholar, half strongman – has proven disconcertingly effective.

The working-class patriot

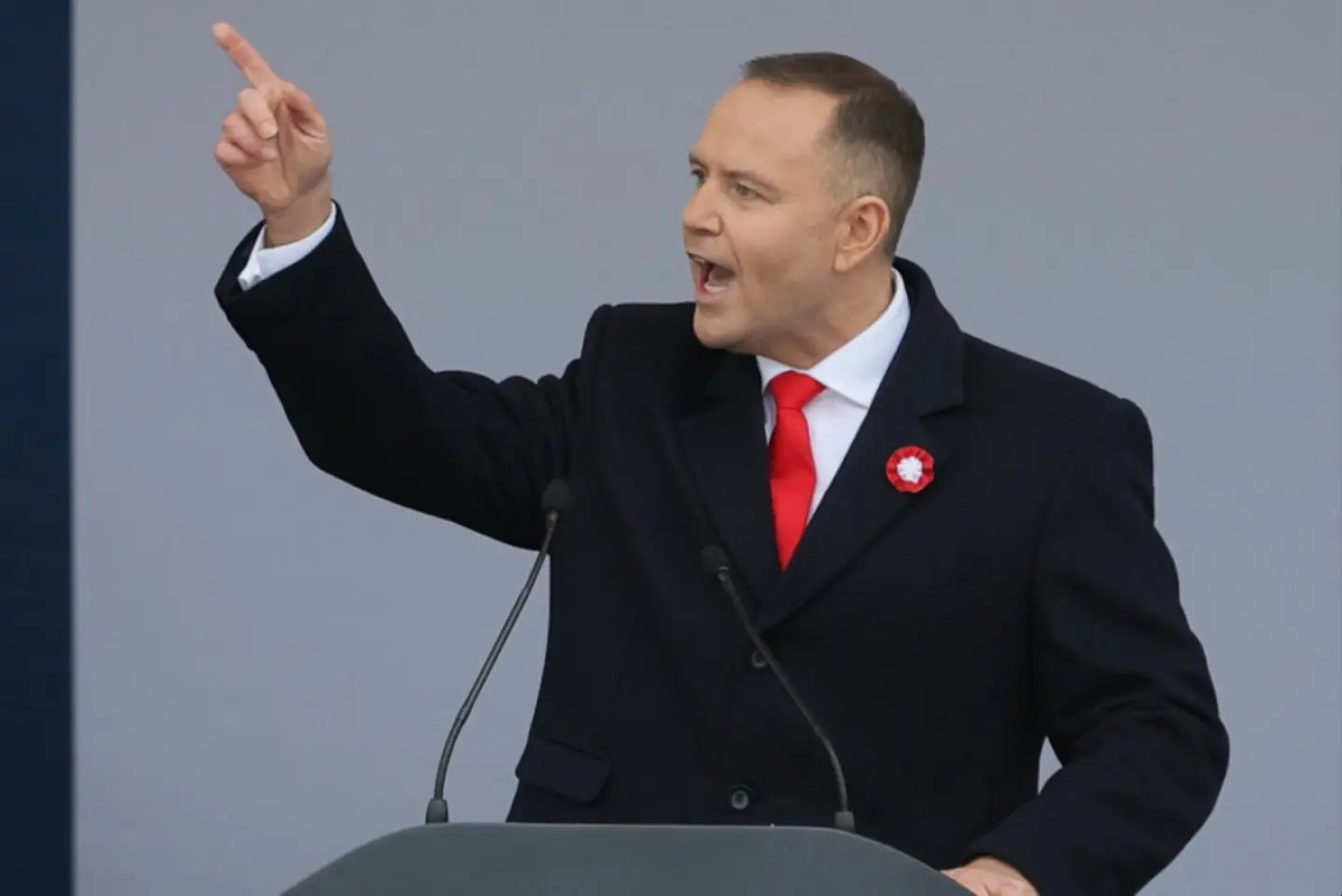

At rallies, Nawrocki cultivates a populist intimacy just like Donald Trump does. “I work hard for all Poles, so that we may live safely in a normal country,” he told a cheering crowd in Mińsk Mazowiecki at his self-styled “hundred-day rally”. “Every decision I make, I repeat: Poland first, Poles first.” The formula has become his mantra.

He boasts of having “signed 70 laws, vetoed 13 and proposed 11,” as if productivity were proof of virtue. Among his legislative proposals are symbolic gestures—tax exemption for families with two or more children, an additional bonus for low-income pensioners, and the resurrection of PiS’s grandiose infrastructure projects such as the Central Communication Port (CPK). None is likely to transform the economy. Most are designed to showcase presidential initiative in the face of a skeptical parliament. “The greatness of a state,” he told his audience, “is that it is strong against the strong, and compassionate to the weak.”

Critics note that none of his flagship pledges – lower electricity prices by a third, a referendum on judicial reform, simplified taxes – has been fulfilled. Even his loyalists admit that “the president can only propose laws, not pass them,” as one of his ministers said. But in populist politics, performance often trumps policy. Karol Nawrocki performs tirelessly.

A palace at war with the government

The defining feature of Nawrocki’s early presidency has been the confrontation with Prime Minister Donald Tusk’s government. The two men share a hometown, Gdańsk, and even a football club – both are fans of Lechia Gdańsk – but little else. Their rivalry is laced with cultural resentment. Tusk represents cosmopolitan liberalism; Nawrocki, nationalist authenticity.

In his first three months, the president has wielded the veto with gusto. He blocked the government’s plan to create the Lower Odra Valley National Park, citing “threats to local farmers,” and refused to confirm nominations of dozens of judges and officers. Tusk accused him of acting as “a violator of the Constitution, not its guardian”. His office retorted that he was defending “sovereignty against ideological experiments.”

The result is paralysis. Poland’s post-PiS institutions are designed for cohabitation, but seldom have they been so tested. Donald Tusk’s ministers speak of “a sabotage presidency.” Karol Nawrocki’s allies counter that the prime minister is “using Brussels as a stick against the Polish majority.”

The symbolism is powerful. To his followers, Karol Nawrocki’s vetoes are acts of defiance; to his critics, symptoms of obstructionism. Either way, they have made him a central actor in Polish politics, overshadowing both the prime minister and his ageing sponsor – Jarosław Kaczyński.

Kaczyński’s creation, Kaczyński’s rival

Relations with Jarosław Kaczyński, PiS’s ailing patriarch, are a mix of reverence and rebellion. During the campaign, Kaczyński presented Karol Nawrocki as the moral heir to “Duda’s legacy.” In practice, he has produced a leader determined to outgrow his mentor.

Inside PiS, grumbling is audible. “He doesn’t come to Nowogrodzka (PiS headquarter is at Nowogrodzka Street), he doesn’t call the leader of the party,” complained one lawmaker to Gazeta Wyborcza. When Kaczyński visited the Presidential Palace, he entered through a side gate – symbolic of the shifting hierarchy. The former IPN director has surrounded himself with his own loyalists: Paweł Szefernaker, a wily strategist, runs the presidential cabinet; Sławomir Cenckiewicz, a controversial historian and former military archivist facing criminal charges for leaking military files, heads the National Security Bureau. Together they form what PiS insiders call “the IPN faction” – a circle of ideologues and ex-colleagues who see themselves as a moral elite rather than a party machine.

The friction surfaced early when Karol Nawrocki vetoed the appointment of Przemysław Czarnek, a PiS heavyweight (former Minister of Education), to head his chancellery. “Two alpha males in one cage – it would have ended badly,” quipped a PiS MP. The episode cemented the impression that the new president intends to build a personal following rather than act as a branch of the party. “He will not repeat Duda’s mistakes,” says a former PiS official. “He will not be anyone’s notary.”

That independence is winning him admirers on the nationalist right. Confederation leaders, once sceptical, now praise his “assertive and courageous presidency”. For PiS, that is both an asset and a threat: a popular right-wing president could reunite the fractured conservative camp – or replace it with his own.

Foreign policy: inappropriate gestures, missed chances

If domestic assertiveness defines Nawrocki’s presidency, his foreign policy has been more erratic. “Every Pole thinks he knows what’s good for Poland’s foreign policy,” wrote Jacek Czaputowicz, a former foreign minister, “but only statesmen can distinguish between opportunity and illusion”. In Czaputowicz’s view, the new president has so far failed the test.

He declined to attend a high-profile summit of EU leaders with Donald Trump in Washington, citing “prior commitments” to bilateral talks – a decision diplomats consider a blunder. Soon after, he rebuffed an invitation from Ursula von der Leyen, the European Commission president, to meet in Brussels. His open letter opposing the EU’s migration pact, in Jacek Czaputowicz’s words, “it missed the boat.”

Most jarring was his public rejection of a visit to Kyiv, after Volodymyr Zelensky invited him in September. “If the president of Ukraine wants to talk, he can take a train to Warsaw,” Nawrocki remarked. “We have good coffee here.” The tone caused outrage. With Ukraine struggling to hold the line in Donbas, Poland’s dismissive stance looked petty. “Such words,” wrote Rzeczpospolita, “betray a stunning lack of empathy.”

To Karol Nawrocki’s supporters, these gestures show independence from Brussels and Washington; to others, provincialism. Either way, they signal that the new president sees foreign policy less as diplomacy than as theatre – a stage on which to assert Polish dignity against imagined slights.

The right’s new centre of gravity

Yet, for all the diplomatic gaffes, Nawrocki’s political position is strengthening. Within the right, he is emerging as a unifying pole. His aides now speak openly of building “a new patriotic camp.” Some PiS figures whisper about a “Nawrocki movement,” modelled on Emmanuel Macron’s En Marche! – though with rather less liberal inspiration.

The ingredients are in place. The president commands attention, controls patronage, and enjoys media amplification from conservative outlets such as Telewizja Republika and wPolsce24. His rhetoric of “strong against the strong, compassionate to the weak” allows him to appeal to both working-class voters disillusioned with PiS’s scandals and younger conservatives who see him as authentic.

Dr Mirosław Oczkoś, a political-marketing expert said that “the president is building a large political camp, and in the longer term, his own formation”. That ambition echoes in Karol Nawrocki’s own speeches. “As long as I serve,” he told supporters, “we will have one mission: 1,725 days of common struggle.” The arithmetic was precise – his term lasts 1,825 days; a hundred are already gone.

Unlike Jarosław Kaczyński, Nawrocki speaks the language of inclusion – albeit selectively. “I work also for those who didn’t vote for me,” he declared in Mińsk Mazowiecki lately. His tone evokes the soft populism of early Andrzej Duda, before the latter became a partisan enforcer. But Nawrocki’s populism is more visceral, steeped in identity rather than ideology.

At times he resembles a Trumpian figure: impulsive, theatrical, obsessed with loyalty. Gazeta Wyborcza dubbed him “the president of chaos” and “a copy of Trump,” accusing him of “paralysing the state”. His critics point to his refusal to appoint 46 judges and several ambassadors as proof that he values confrontation over governance. “He doesn’t seek compromise with the Tusk government,” the paper warned. “He wants to destroy it.”

Supporters counter that he is restoring balance to a system dominated by liberals and technocrats. “He defends ordinary Poles against the arrogance of elites,” says Adam Andruszkiewicz, his deputy chief of staff. In the short term, this populist posture works: it secures media oxygen and keeps the president above the fray. The long-term cost – erosion of institutional trust – seems a lesser concern.

Foreign headaches

Abroad, Poland’s partners are watching uneasily. The European Commission views the president’s vetoes as obstacles to re-aligning Warsaw with the rule-of-law standards that unlock EU funds. Berlin notes with irritation his revival of nationalist rhetoric about “sovereignty.” In Washington, diplomats whisper that “Nawrocki fatigue” is spreading. His absence from the August Trump-EU summit and his brusque attitude toward Ukraine have not gone unnoticed.

Within NATO, Poland remains a key eastern-flank power; Nawrocki’s gestures have not altered that reality. But his symbolic snubs complicate coordination. When Ukraine invited him to visit the front lines, his public refusal prompted awkward questions in Brussels about Poland’s reliability as Kyiv’s advocate. “It was like watching a neighbour slam the door during a fire,” says one European official.

For now, Prime Minister Donal Tusk reassures allies that Poland’s foreign policy remains steady. But should the president use his constitutional powers to block defence appointments or ambassadorial nominations, that reassurance may ring hollow.

The image-maker and the message

Public opinion remains sharply divided, but not along simple lines. Polls show that men, rural voters, and those with secondary education rate him most favourably; women and urban professionals are less impressed. Among young voters, he has achieved a rare feat: enthusiasm. His TikTok-style campaign videos, peppered with boxing metaphors and patriotic imagery, resonate with the same demographic that once flirted with Confederation Party.

Still, among liberals, his image is toxic. “He looks more like someone from a hooligan brawl than a president,” complained one voter interviewed by OKO.press. Another described him as “a vindictive nationalist.” The contrast between admiration and disdain is almost sociological: to one half of Poland he is a patriot reclaiming dignity; to the other, an embarrassment in a black T-shirt shouting slogans at football fans.

That polarisation suits him. Populists thrive on moral combat. As long as Donald Tusk embodies the urban elite, Nawrocki can pose as the man of the people – without actually delivering much to them.

Few modern Polish presidents have so self-consciously managed their image. Karol Nawrocki’s social-media team, led by Adam Andruszkiewicz, floods the internet with cinematic footage of the president greeting farmers, visiting factories, or shadow-boxing in gyms. He is portrayed as an everyman, disciplined yet approachable. His slogan – “Strong Poland, Strong Families” –appears under every post.

The aesthetics are deliberate: fewer suits, more rolled-up sleeves; fewer conferences, more stadiums. It is politics by muscle memory. “He’s learned that charisma in Poland is physical,” says a communications adviser. “People want to see strength, not procedure.”

That formula may work at home, but abroad it invites ridicule. Western media caricature him as “the boxing historian,” a man equally at ease quoting patriotic poets and trading jabs on social media. For a leader seeking European respect, the line between authenticity and caricature is thin.