Squeezed between its own regional ambitions and those of global players, between domestic challenges and its own policy errors, the current regime in Ankara speaks and acts in an increasingly erratic manner. And the consequences are difficult to foresee at this stage.

The coups and protests that fuelled Erdogan’s authoritarian drive

Starting approximately in 2010, the Erdoğan-AKP regime initiated a domestic strategy to increase its control over the judiciary. This already ran fundamentally against Turkey's commitments as NATO member and candidate to European Union (EU) membership. The process was accelerated multiple times, each following important events abroad and at home, which pushed the regime in a defensive posture. Regional developments came first.

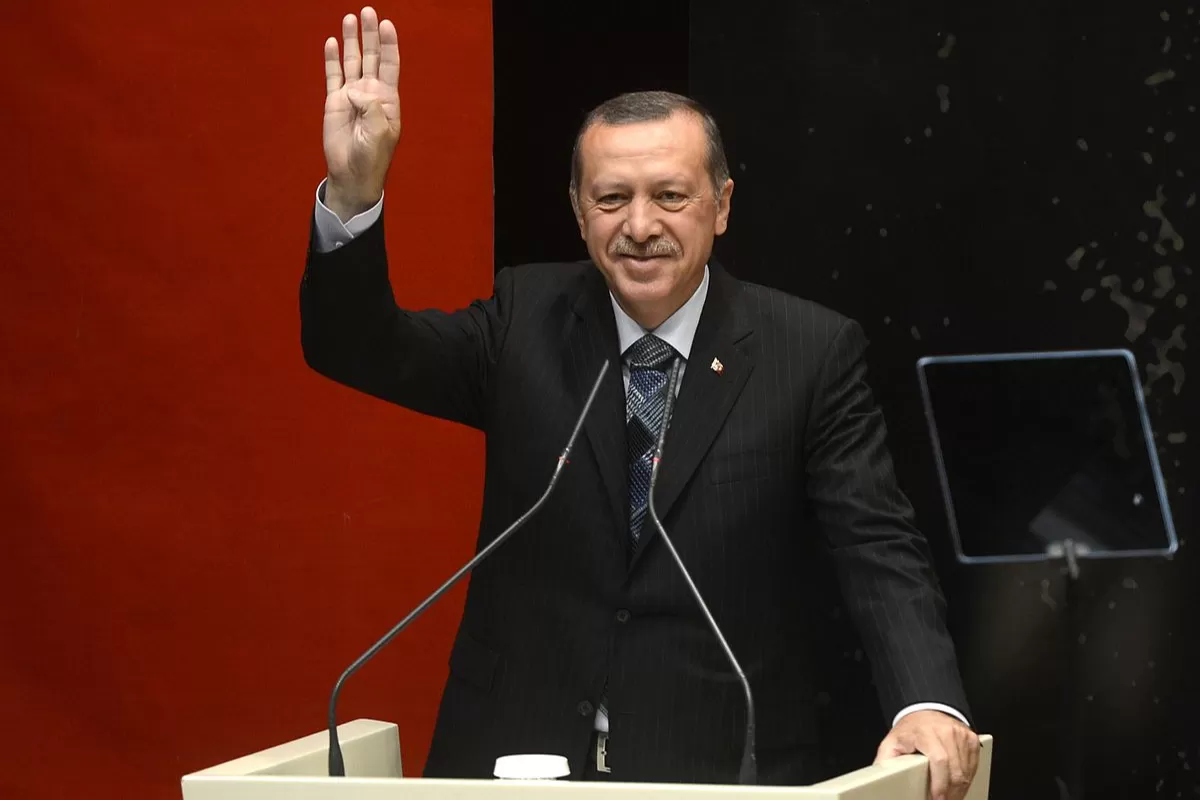

The Erdoğan-AKP regime has been a major supporter, together with Qatar, of governments emanating from the anti-Western Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt, Sudan, or Libya. The Turkish President makes the organisation's Rabia sign, sometimes with both hands, at all public rallies. However, such commitment implies the continuation of strained relations with the Arab governments, especially the powerful Arabian kingdoms, who treat the Brotherhood as a terrorist organisation. Significantly, Russia also treats this organisation as terrorist, while not labelling as such the PKK, which had an office in Moscow for many years. Nevertheless, international pressure on the Turkish side to give up support for the Brotherhood was one important factor determining its authoritarian turn. This can be interpreted as a reflex of self-preservation after the Brotherhood-affiliated governments begun to fall.

First came the 2011 military coup that ousted the democratically elected Morsi government in Egypt. Eight years later, in April 2019, another military coup ousted Omar al-Bashir, the long-time ruler of Sudan and a prominent Islamist. Following that episode, Sudan's new administration became an essential partner of Egypt in the campaign against the Brotherhood, with support especially from the Saudis, the United Arab Emirates, and possibly Israel. Erdoğan's Turkey remains on the side of the anti-Western Brotherhood, which impacts negatively its relations with most countries in the region.

Domestically, the regime's authoritarian turn followed the so-called "Gezi Park protests" in the summer of 2013 and the major graft case unveiled in December 2013. The latest was blamed on the Islamist leader Fetullah Güllen and his supporters, who had been essential allies during the accession of Erdoğan-AKP to power. The conflict between the two camps culminated with the failed coup attempt of July 2016. By then, Güllen and his supporters were formally denominated as Fetullah Gülen Terrorist Organisation (Turkish acronym FETÖ) and treated as such under the country's drastic anti-terrorism legislation.

Following a highly contested referendum in 2017, Turkey switched in 2018 to a Presidential system that subordinates all government branches, including the judiciary, to the Presidential office. The historical steps indicated above are described by some as leading to the establishment of "Erdoğanism". The term refers to President Erdoğan's personal rule building on electoral authoritarianism, neopatrimonialist economics, and political populism, all underlined by a Turkish version of political Islam. All the above would have been enough to set the country on a collision course with the secular, liberal democratic principles governing Western (European and North American) democracies.

However, the regime in Ankara did not stop there and also adopted a nationalist conservative, anti-Western stance in its foreign and security policy. This seems to have been triggered by suspicions about the role allegedly played by the US and certain European countries in the 2011 military coup in Egypt and, domestically, in the 2013 Gezi Park protests and the failed coup of 2016.

Going East: A NATO country shopping for Russian guns

To this must be added the frustration of Turkish strategists and decision-makers about the reluctance of Western countries to share military technologies with Ankara. Erdoğan and high officials of his executive team invoke this aspect when justifying the 2019 acquisition of the S-400 anti-aircraft missile systems from Russia: the Pentagon did not share the Patriot technology with Turkey. No word, of course, about the fact that Moscow does not share the S-400 Triumph technology with Turkey either. Moreover, the S-400s are already outdated and even overrated, soon to be supplemented with the S-500 Prometheus and other elements. And Erdoğan's offer, two years ago, for bilateral cooperation on the production of the S-500 systems remained again unanswered by Vladimir Putin.

Ankara is also frustrated because it lacks high-end engine technology for military vehicles and aircraft. It was expelled from the F-35 programme under the Countering America's Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA) in July 2019. Encouraged by certain successes of the domestic defense industry, the government pushes ahead with the project of the first Turkish-made fighter jet, the TAI TF-X. However, it was repeatedly refused the supply of engines for that project by Western partners fearing CAATSA sanctions. Recently, a deal was signed with a local company for the development of jet engines. It is nevertheless hard to believe that the Turkish aeronautical industry will be able to produce such high technology in the absence of some sort of imports from the West. The same applies to the combat drones produced by Baykar Makina, very successful in northern Syria, Libya and Nagorno-Karabakh. Even the latest, most advanced model relies on foreign and Turkish technology that will soon be outdated and possibly easy to beat by producers in the West or East if needed in the future.

Overall, Turkey's adventurous S-400 deal, together with risky, peace-threatening involvements in regions such as northern Syria and the Eastern Mediterranean, Africa and the Caspian represent altogether a serious deviation from the country's traditional posture in the Western alliance. And Russia continues to tempt Ankara with a veiled invitation for negotiations on the purchase by Turkey of Russia's Su-35 and Su-57 fighter jets. Again, Moscow uttered no word about the possibility of technology sharing, but the discourse from Ankara remains, for now, in the logic of a continued Russian-Turkish partnership.

Presidential spokesperson Ibrahim Kalın, the government's voice especially on foreign relations, recently gave an important expression of the predominant feelings and attitudes at the top of the regime. In a televised interview for Haber Global, he stressed that "there will be no turning back" on the issue of S-400s, this being "our decision as a sovereign country making a deal with another sovereign country" (for an English transcript, access here).

Although he said that relations with the US, NATO and the EU "will continue", Kalın used very strong and rather undiplomatic words when detailing. Thus, the CAATSA sanctions are "meaningless" for the current regime in Ankara. About the EU, he said that it is a union that "turns to Washington for all the most critical issues [...] which makes Europe an actor that has no effect on global events". Significantly, he contrasted the stance of the Erdoğan-AKP regime with "the inferiority complex present in previous [Turkish] administrations." In conclusion, the view in Ankara now is that Turkey is an equal of the US and EU in foreign policy and that its positions need to be taken into account. No similarly toned words for Moscow at the moment. The official discourse indicates therefore that the "eastward turn" is not negotiable and cooperation with Moscow on critical security issues moves ahead. However, Ankara is not putting all its eggs in the Russian basket.

Flirting with Ukraine and US allies from across the world

Concerning military technology procurement, Turkey has actually worked quite hard to develop cooperation schemes with actors other than Russia. After the invasion of eastern Ukraine and the occupation of Crimea, in 2014, relations between Ankara and Moscow have soured and Turkey has constantly expressed its support for the sovereignty and territorial integrity of Ukraine.

Since 2014, Ankara has intensified military exchanges with Ukraine, from exports of military ammunition valuing millions of dollars in 2015 and 2016, to more sophisticated forms of cooperation. After 2016, bilateral deals covered cyber-security, radar and radio systems, and combat unmanned vehicles and drones. In 2018, an important deal was signed under which Ukraine purchased Turkish Bayraktar TB2 drones. This is seen in Ankara as a first step to solving the old problem of the Turkish military industry: the incapacity of developing turbo prop and diesel engines. The plan is to produce such engines for Turkish military vehicles and for the Atak II-class T929 helicopter using Ukrainian technology. The two countries also work together on plans to jointly produce the Bayraktar TB2 drones and modernize other military assets, ranging from tanks to anti-tank missiles, combat vehicles, helicopters and airplanes.

As indicated in the previous section, Ankara also increases reliance on domestic producers of military technology. In yet another search for non-Russian solutions, Turkey pushes now for cooperation with Pakistan on the joint production of missiles and warplanes, which may mean access to Chinese technology. It remains to be seen how fruitful this new plan is and how Western partners react to it. Ankara also secured a deal on cooperation between the local vehicle maker BMC and two South Korean companies. They will produce together an engine for the indigenous Altay battle tank, which was another old problem of the Turkish arms industry.

Trying to shake Russia’s grip on Turkey’s energy supply

In the energy sector, too, the current regime in Ankara has actually worked with success on alternatives to supplies from Russia, or from Russian-controlled sources. And that is despite the continued collaboration between the two sides on the nuclear plant at Akkuyu and the TurkStream natural gas pipeline from Russia to northwestern Turkey.

Indeed, Russia consolidated its dominant position in Turkey's energy sector after the 2014 aggression in Ukraine, providing between 45 and over 50 per cent of Ankara's needs. However, official statistics indicate significant change in this sector starting in 2019. It is difficult to identify the causes of the shift, although a number of events have certainly impacted the level of mutual trust. Among them can be counted the downing of a Russian fighter jet by a Turkish one near the Syrian-Turkish border in November 2015 and the Russian response by temporarily banning Turkish imports and the access of Russian tourists to Turkey. One should also not forget the clashing interests of Moscow and Ankara in Syria, Libya and Nagorno-Karabakh.

What is nevertheless certain is that, given especially its massive current account deficit, to which energy imports contribute 75 percent, Turkey has worked intensively in recent years to reduce dependency on expensive Russian and Iranian pipeline gas. In March 2020, it imported for the first time more gas from Azerbaijan (924 bcm) than from Iran (557 bcm; 33 percent decrease from March 2019) and Russia (389 bcm; 72 percent decrease from March 2019). Additionally, Ankara has increased imports of liquefied natural gas (LNG), especially from Qatar and the US, which surpassed pipeline gas imports for the first time in March 2020 (2.06 bcm of LNG, accounting for 52.5 percent of the total gas imports that month).

With hard times upon it, Turkey is looking west for a way out

Certain public declarations and policy steps taken of late by the Turkish government clearly show that Ankara is, once again, courting its old friends and partners. This must be linked with a deepening economic and financial crisis, the fall of the lira since August 2018 and poor governmental management overall ever since, under the tight presidential system. Now, consumer inflation is above 15 per cent and producer inflation is around 25 per cent. According to official statistics, the unemployment rate stands a bit above 13 per cent, but alternative sources place the actual rate at nearly 30 per cent, with the youth being highly affected. Additionally, long-term foreign investments continue to keep away from a country in perpetual need of foreign, especially Western capital accompanied by technological investments. The most cited cause is Turkey's poor record concerning human rights and judiciary independence under the Presidential system, plus tensions with neighbours.

Pressed to change course, Ankara resorts to various strategies. The President and other high officials try to re-open channels of dialogue with important partners, although to no avail for now. Israel has remained silent about the discourse of reconciliation emanating from Ankara. The same deafening silence comes from Washington, where the new President has yet to call the Turkish leader after starting the job at the White House.

Egypt, on the other hand, is more assertive. It has conditioned the restoring of bilateral relations on Ankara withdrawing forces from Libya and stopping its escalatory strategy in the eastern Mediterranean. However, the rift between Erdoğan and Egypt's Abdul Fattah al-Sisi runs much deeper. The Turkish leader's open support for the Muslim Brotherhood and personal enmity to al-Sisi, punctuated with insulting remarks and gestures in the past, remain serious hurdles for now.

Erdoğan's recent pledges to reform the country's politics and economic policies fell on deaf ears in Europe, too. Some important European leaders first of all cannot forget that they have also been insulted repeatedly in the past by the Turkish leader and his acolytes. Additionally, some Western intelligence agencies and mass media warn about the increasing influence of Ankara on the Turkish diaspora in Europe. One recent case is about criminal threats sent to a German left-wing female politician of Kurdish origins. The written threat was signed by JITEM, an ultra-nationalist gendarmerie cell responsible for assassinations of leftist and Kurdish militants in Turkey in the 1980s and 1990s. The coming back to life of this group, together with the increasing influence of other ultra-nationalist groups among Turkish emigrants, may already represent a threat to societal and institutional stability in Europe. They also damage seriously the international image of the current Turkish regime. Although this may not be enough, European leaders continue to wait for concrete reforms in Turkey, in line with the EU's enlargement conditionality, and not just words promising change.

Stuck in a geopolitical limbo

While profound reforms may actually never crystallise under the Erdoğan-AKP rule, some steps (indicated above) have been taken that seemingly signal at least some sort of distancing from Moscow. There may be a degree of perception change taking place in Ankara and the main push is coming from the citizens.

With the economy in tatters, Turks feel in their everyday lives that things go in the wrong direction. Public support for the government's nationalistic stance has thus diminished and more people consider now that improvement in the economy depends on the country joining the Union and on returning to the parliamentary system of government. Although distrust of the US and Western European countries remains high, polls indicate the constant support, of over 50 per cent over the last four years, for Turkey joining the EU.

However, given the record of the Erdogan regime, there’s not much reason for being optimistic about the possibility of this country actually returning to the agenda of reforms, in line with the EU membership conditionality. Some steps away from Russia, as evidenced above, do not mean decisive steps toward the basic norms of liberal democratic governance.

In fact, Ankara's apparently positive overtures to traditional Western partners may only be indicators of panic, of identity crisis and loss of compass. After advancing remarkable domestic reforms and a foreign policy of cooperation in the early 2000s, the Erdoğan-AKP regime eventually gave in to nationalist hardliners. It renounced the westward oriented path of liberal democratic change and shelved indefinitely a political, democracy-based solution to the never-ending "Kurdish issue". These were replaced by a so-called "Eurasianist" logic advanced by anti-American and anti-European nationalists, in spite of informed predictions that such logic of government would be damaging to Turkey. Aggressiveness in Syria and Libya, or aggressiveness toward Israel, Egypt, Cyprus and Greece in disputes over energy in the Aegean and eastern Mediterranean regions brought nothing positive. Such attitudes and actions only increased the number of adversaries and cemented the impression that the agenda of the current regime is increasingly foreign to the long-term interests of Turkey and Turkish people.