With a new coalition, promising hefty reforms and ending an almost year-long stalemate, Bulgaria seems to be heading towards a change in 2022, after a chaotic 2021. On an international level, the broad coalition, which features parties all along the right - centre - left spectrum, is expected to have more inclusive politics towards Northern Macedonia, keep a healthy distance from Moscow, treat with a better care and transparency small and middle businesses, increase the slow vaccination rollout threatening Bulgaria of continuous cycles of infection waves. And in the long run, adopt the euro currency.

It is the promise of a new beginning, after a decade marked by GERB domination and suspicions of corruption. For the younger generation, it may as well be a new 1989 moment.

@Edward Serrota, People dancing in front of the burning former building of Bulgarian Communist Party, August 1990

An endless cycle of new beginnings

“Believe me: there will be a zero tolerance for corruption and for every lev that goes in the wrong place,” new Prime Minister, entrepreneur, former interim Minister of Economy and We Continue the Change co-leader Kiril Petkov, said from the parliament stand on Monday, when the coalition was officially green-lighted by the MPs.

On a closer look, the coalition led by political newcomers and winners of the November 14 elections “We Continue the Change”, an after-effect of the 2021 interim government, reminds of the fast rise of other political novices who were seen as white hopes, engaged with people educated abroad who came back to contribute but left office with a highly compromised reputation.

The prime example of this is that of former king Simeon Saxe-Coburg-Gotha (Simeon II, son of Boris III of Bulgaria) who came back after decades in exile and was elected Prime Minister of the Republic of Bulgaria from 2001 until 2005, only to completely lose societal trust by the end of the decade and pave the way for the autocratic politics of former Sofia mayor and PM Boyko Borissov and his party GERB, officially pro-EU and centre-right, yet continuously associated with corruption allegations, diminishing media freedom (Bulgaria is currently 111 on the World Press Freedom Index), amassing power through oligarch ties and mismanagement of public funds.

In a strange way, in 2021 Bulgaria is looking like rewinding the clock back to 1989 by turning its back on a repressive ruling class, in search of new heroes without a solid guarantee they’ll bring the long-needed change. Bulgaria’s version of democracy has also resulted in instinctive voting tendencies and short historical memory from a distrustful society.

The never-ending “transition”

In Bulgarian media, the “transition” (“преход”, “prehod”) refers to the era when, after the repressive Communist Regime fell apart in November 1989 and leader and Bulgarian Communist Party strongman Todor Zhivkov stepped away from power, the country made a painful slide to capitalism. The process of lustration started but is now widely seen as incomplete or even a downright failure despite leading to relative economic stability in the 2000’s and Bulgaria joining NATO in 2004 and the EU in 2007. “By joining the EU, Bulgaria has proved that it has inclusive institutions - at least on paper. In fact, our institutions are largely of a different kind, and this is the main reason for the country's disappointingly slow progress”, says financier and analyst Evgeniy Kanev for dnevnik.bg in an interview from January. “It is easy to establish that the Bulgarian political system is one that exhausts the resources, it has been promoting representatives not of the taxpayers, but of the political elite.”

After November 10 1989, The Bulgarian Communist Party gave up the monopoly of power, rebranded itself as Bulgarian Socialist Party (BSP) but in the three decades that followed it never managed to go beyond its pro-Kremlin stances and despite the official left status, the party is increasingly associated with conservative rhetoric. In the 1990s, the Union of Democratic Forces ruled between 1992-1994 following multi-party elections and then BSP again took over in 1995-1997, leading the country to an inflation and economic collapse. Meanwhile the presence of an “invisible state” became more and more apparent and the country witnessed the birth of a tycoon class, more or less directly influencing local politics. The Democratic Forces came back in 1997 and with Ivan Kostov as a Prime Minister, Bulgaria managed to pass successful economic reforms leading to first EU ascension talks in 1999.

However, unemployment and shadowy privatization deals have plagued the era. "There are these decades that you feel have lasted a lifetime. Or they change your life irreversibly. The 90’s were and are such a decade. And not everyone came out of it. And few of those that came out remained the same”, writes novelist and poet Georgi Gospodinov in an essay from the omnibus book “Stories from the 90’s” (ICU Publishing, 2019).

Promises for fast reforms have been a catchphrase ever since. After Simeon II, who on his first TV interview in 2001 claimed he would “fix” Bulgaria “in 800 days”, entered politics, his party NDSV ruled until 2005. After dissatisfying results on the next general elections, NDSV eventually formed a coalition led by the Bulgarian Socialist Party and including the Movement for Rights and Freedoms, a controversial party, focused on the Turkish diaspora in Bulgaria, continuously associated with corruption and oligarch ties. The three-way coalition led the country until 2009.

Boyko Borissov’s downfall recalls Communist leader Todor Zhivkov’s fate

Meanwhile, the figure of Boyko Borissov became more and more visible. Former bodyguard of Todor Zhivkov and Simeon II, and with numerous debatable points in his biography and qualifications, Borissov became Chief Secretary of the Ministry of Interior in 2001 and in 2005 was elected Mayor of Sofia in 2004. Borisov's GERB won the parliamentary election in July 2009 by collecting 39.72% of the popular vote. The party has been at the center of local politics ever since and Borissov, in his role as a long-serving Prime Minister, often the only internationally recognizable Bulgarian politician in the 2010’s.

What remained as a constant feeling during the long “prehod” is that Bulgaria is being ruled by outside and oligarch forces. The political elite was called “mafia” even by President Rumen Radev, opponent of Borissov, in 2020, and is commonly referred in Bulgarian as “the status quo”.

The citizen unrest unlocked several protest waves, most notably in 2013-2014 and 2020-2021, also resulting in low voter turnout in recent elections (usually below 50 per cent of the eligible voters take part in the process) and continuous immigration to the West as well as internal migration from depopulating villages to towns. For those not on the streets, apathy became dominant. The distrust of authorities and the intentions of the state might also be tracked in events such as Bulgaria’s slow vaccination rollout (around 25 per cent of the population is inoculated).

In the last few years of his serving as a Prime Minister, the similarities between Boyko Borissov and Todor Zhivkov became more and more apparent, especially as GERB became a controlling power of local assets, mayors and business opportunities (2021 brought further extortion claims from businessmen to members of GERB). By portraying himself as an only option for Bulgaria to move forward and playing it close to the small man by visiting small villages rather than giving interviews on TV, Borissov made a long run, stopped by the thirst for change and his inability to control every controversy around the party. “The country’s dizzying daily headlines feel more like plotlines from a hit mafia series on Netflix than actual events unfolding in a European Union member country”, wrote Politico in June.

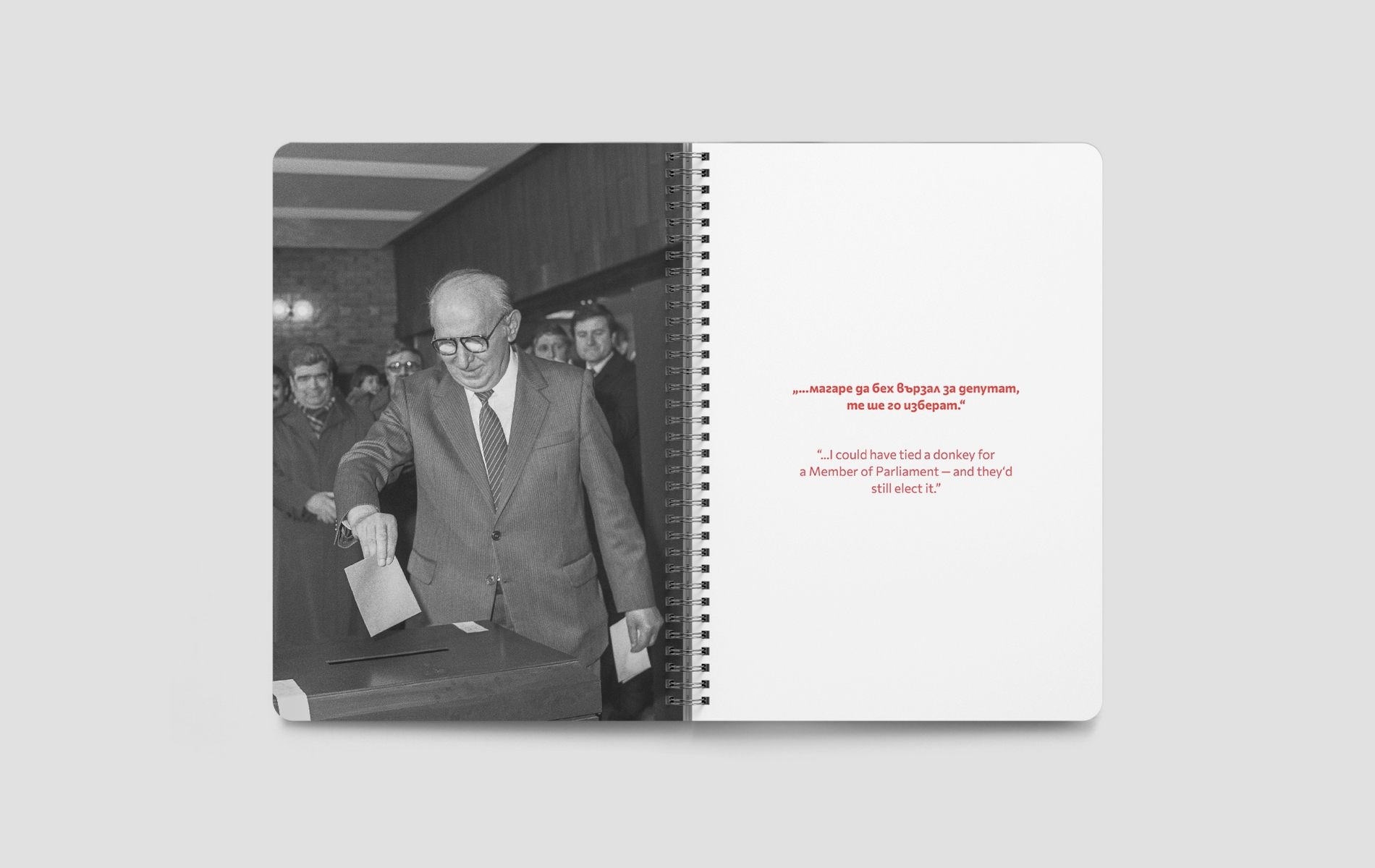

From the photobook "He Breaks He Cuts He Spills" by Nikola Mihov who places quotes by now former PM Boyko Borissov along with one-time Communist leader Todor Zhivkov to highlight the similarities between them.

Part of the challenge to decode Bulgaria’s political climate is that the country looks different from the outside and from the inside. Borissov often appeared light-hearted and non-confrontational in international meetings while adopting a much harder and populist tone in local appearances. His unofficial allies from the Movement for Rights and Freedoms are often treated as liberal abroad while associated with numerous controversies at home: in 2021 party member, former media mogul and oligarch Delyan Peevski was sanctioned under the Magnitsky Act and US Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control, in result part of his assets were frozen. He was also mentioned in the Panama Papers leak.

2020-2021 saw GERB’s reputation falling further and Borissov entering survival mode.

How Bulgaria is looking at the end of 2021

Bulgarians have voted in a total of five elections this year - three general after inconclusive results and two rounds of presidential elections.

Borissov came out bruised from the April general elections where GERB won in a razor-edge battle with newcomers There’s Such People, founded by popular TV showman Slavi Trifonov and losing the vote in Sofia for the first time to Democratic Bulgaria. GERB became isolated in a parliament full of opposition parties, albeit fragmented. On the repeat elections, There’s Such People made a historic win, however their inability to secure a coalition, made them seen as chaos agents with no long-term vision.

Meanwhile, the President Radev-appointed interim cabinet grew in public trust for its desire to revise GERB’s wrongdoings. Two of the former interim ministers, entrepreneurs Kiril Petkov and Assen Vassilev, created “We Continue the Change”. Although most polls indicated the new anti-corruption party would get elected to the parliament, hardly anyone predicted the party can debut directly as a first political power. They won with 25.67 per cent of the votes, leaving GERB second.

In a bid to show transparency, the party live streamed several of the coalition talks with Democratic Bulgaria, Bulgarian Socialist Party and There’s Such People. On Monday the coalition officially assumed power, for now easing the political crisis while Borissov’s GERB and Movement for Rights and Freedoms are now in their new roles as opposition.

Some of the rhetoric of “We Continue the Change” feels similar to promises made by politicians in the early 2000’s - that a strategy to bring back Bulgarians abroad through better work and living opportunities should be created and the “brain drain” should be stopped.

“The state is so deeply immersed in oligarchic interests that gradually winning back pieces of it would be the big change”, says political analyst Anna Kraseva to newspaper Capital Weekly. “The point is not to create a new oligarchy to replace the current one. This is the profound change that citizens expect.”

“Bulgaria will be a very different place in four years' time”, co-leader of We Continue the Change and new Prime Minister Kiril Petkov said on Monday. The party is expected to continue its good relationship with President Rumen Radev, recently re-elected and in this way, solidify his increasing profile.

For the younger voters, the downfall of Borissov most probably feels similar to how first-time voters fell in the early 90’s: a figure that overshadowed every other politician for years is suddenly away from the spotlight. Much like Bulgarian Communist Party’s legacy, GERB’s past will be a source of controversies and revisions for years to come.