In theory, Romania is not overly reliant on Russia in economic terms. Trade relations are limited, the number of Russian companies operating on the Romanian market is relatively small, and Romanian imports of oil and gas from Russia are incomparably lower compared to those of other EU countries. Over the years, however, Russian oligarchs, most of whom are connected to the Kremlin, have taken possession of huge chunks of certain sectors of the Romanian economy. Adding to these economic levers are political ones too – there are Romanians who, consciously or not, are playing into Moscow’s hands. It’s a strategy Russia has been applying ever since the 1990s in most ex-communist states.

Russia’s strategy in ex-communist states: networks of influence and investments in key sectors of the economy

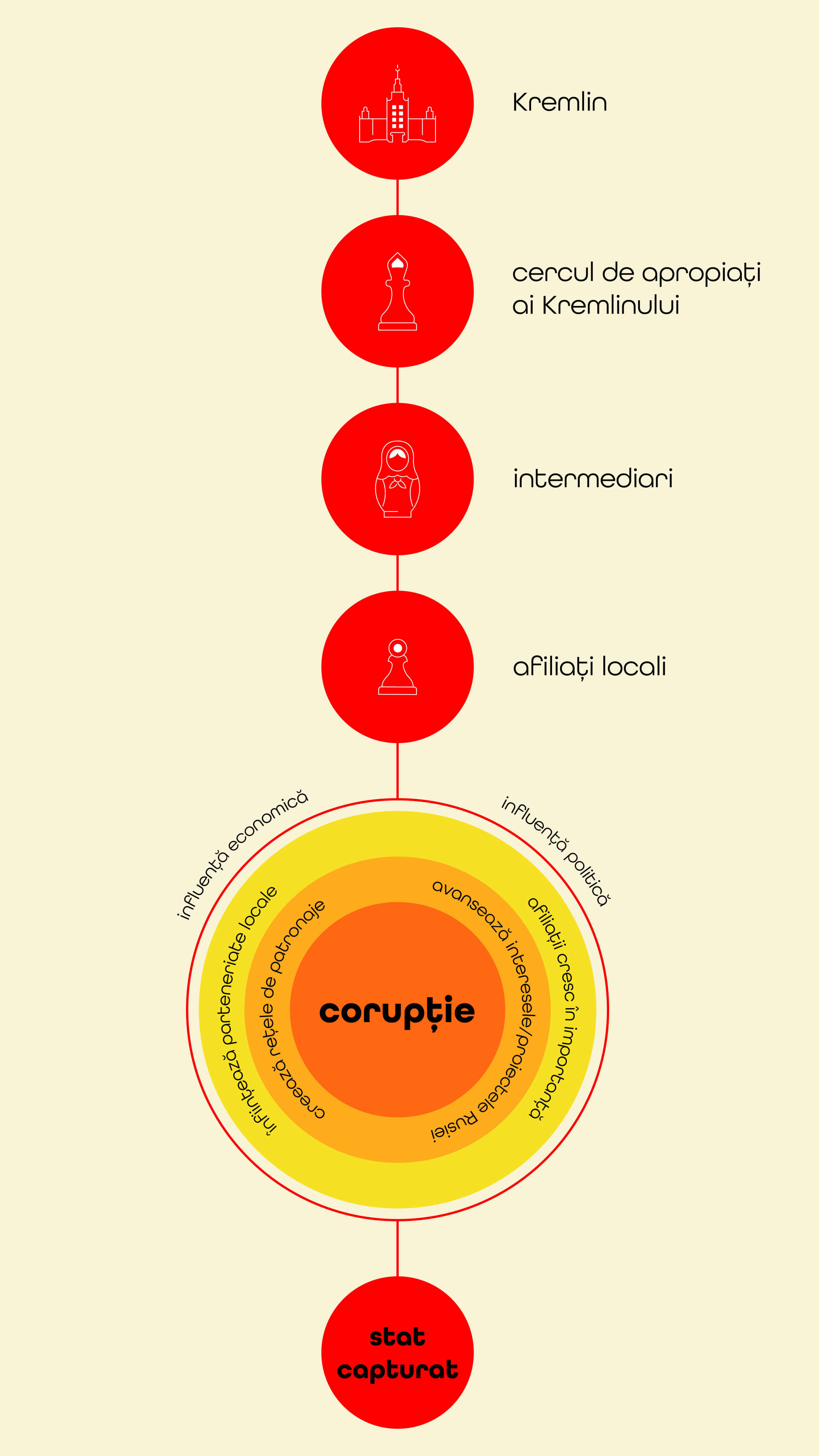

After the collapse of communism, Russia tried to rehash its strategy to defend its own economic and security interests in the former satellite republics of the Soviet empire, including in Romania. The strategy in question focused on two main lines of action. First, developing a network of influence among politicians and decision-makers at local level. The corruption/corruptibility of the local elites helped achieve this goal. Second, investing in key areas of the countries’ economies. Having infiltrated the political class and once it seized control of key sectors of the economy, Russia was now able to expand its own influence and foster its own interests.

Artboard: Veridica/Iulian Preda

Experts with the Center for Strategic & International Studies (CSIS) think-tank in the USA have drafted three reports on this issue in recent years, all part of “The Kremlin Playbook” series. The first report describes how the Russian network works: “Russia has developed an inscrutable network of patronages in the region, which it employs in order to influence or direct political decision-making. This web resembles a network-flow model, which we describe as a “unvirtuous circle” of Russian influence. The circuitous flow can either begin with the Russian political or economic penetration and from there expand and evolve, in some cases leading to “capturing the state”. Russia seeks to gain influence over (if not fully control) certain state institutions of critical importance or the economy and uses this influence to shape national policies and decisions. Corruption is the lubricant based on which the system operates, focusing on the exploitation of state resources in order to further develop Russia’s networks of influence”.

The second episode of the Kremlin Playbook advances a case study focusing on Romania and the Russian influence in this country. The study concludes that at no point was Romania any less infiltrated by Russian interests compared to other countries in the region. At the same time, however, CSIS experts argue that Romania remains vulnerable to the Russians’ actions: “Romania has the weakest political and economic ties to Russia of all the case study countries, but Russian malign influence has still entered the country’s bloodstream through the exploitation of institutional, political, and societal weaknesses—particularly corruption. For example, non-transparent privatizations have opened the door to Russian investors, particularly in the metallurgy sector”.

Another strategy employed by the Russians was to further robust economic ties with various companies in key sectors across Western Europe. According to the Kremlin Playbook 2, Moscow employs so-called “enablers of Russia’s malign influence, those who promote the Russians’ interests, allowing them latter to achieve their strategic goals and avoid some of the consequences of their behavior”. The list of enablers includes a company with a key role in the oil and gas industry in Romania, the Austrian company OMW, which in 2004 won the privatization tender for Petrom, the most important state-owned company in oil and gas sector. The Kremlin’s connections with these Western enablers makes it even more difficult to monitor Russian influence in EU economies, all the more so as the interactions themselves are not fully transparent.

There’s one final aspect we should consider as part of this discussion. In theory, only 600 companies with Russian capital operated in Romania in 2021, accounting for 0.25% of the sum total, which translates into a subscribed share capital of merely 37 million EUR. Nevertheless, in practice, Russian investors resort to third parties or open branches in European countries such as the Netherlands, Cyprus or Switzerland, or set up offshore companies in tax havens. Thus, the number of companies controlled by Russian investors is artificially diminished in official records.

Russia and the Romanian steel industry: shady privatizations, state aid and financial fraud

There are plenty of examples of Russian businesses operating in Romania, yet there are three sectors in particular that Russia has been chiefly focusing on: metallurgy and steelworks, aluminum and raw materials, aluminum oxide and the industrial pipe industry. We’ve selected three stories for each of these sectors as telling examples of how the Russian network described above actually operates.

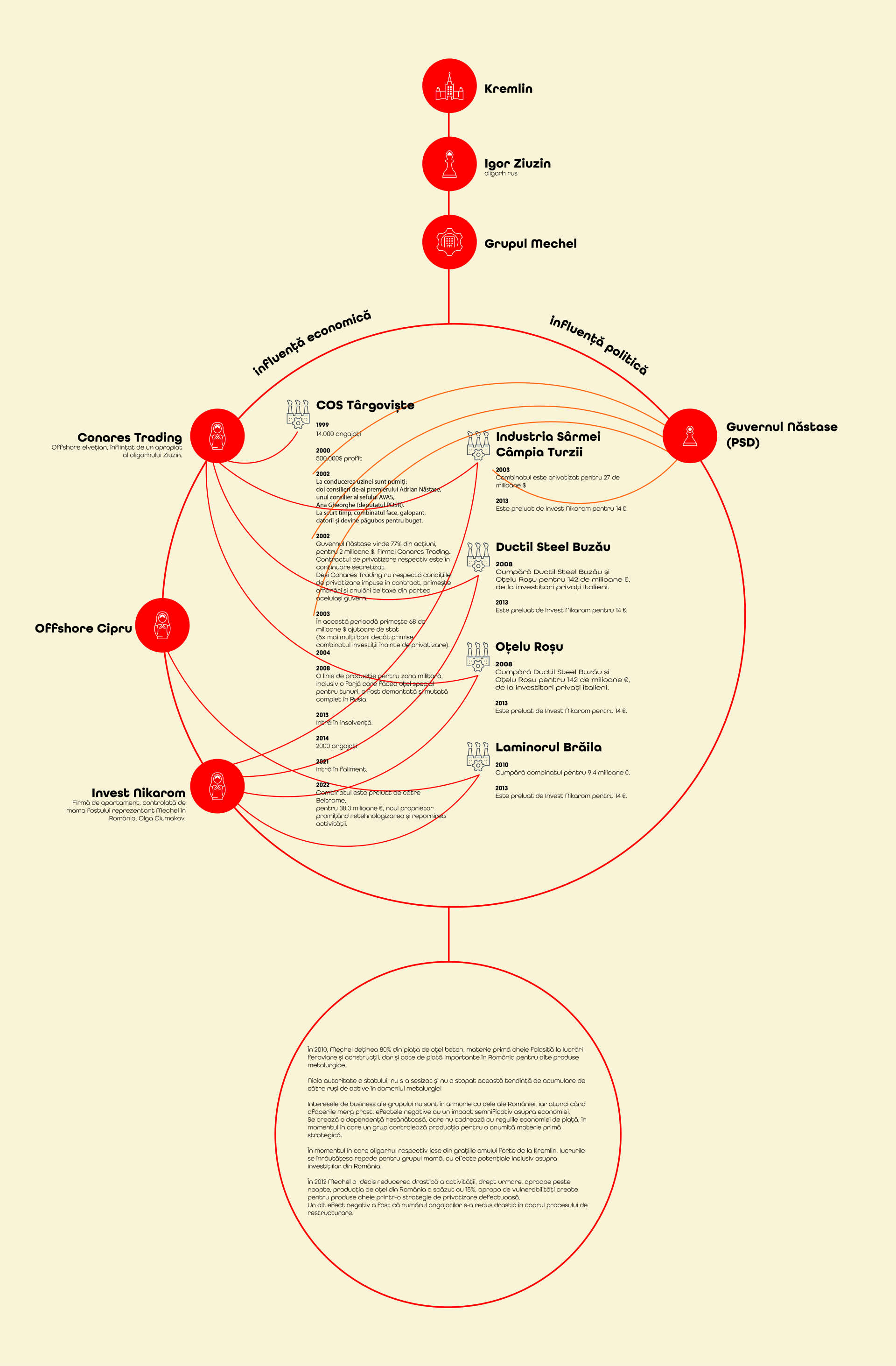

We’ll start with Mechel, a consortium operating in the field of metallurgy, which has been very active in Russia in the last few decades. At one point, in the early 2000s, the company’s chairman, Igor Zyuzin, set his eyes on a few production plants in Romania. He had set up the group Mechel in 2001 by taking over the Chelyabinsk Metallurgical Plant, the second largest such plant in Russia, buying it off Glencore International, led by the US billionaire Marc Rich. Zyuzin also exploited a number of coal mines in Russia. His ventures in Romania started in 2002, when Mechel bought the Târgoviște Special Steelworks Plant (COS).

Chairman of the Board of Directors of Mechel Igor Zyuzin attends the congress of Russian Union of Industrialists and Entrepreneurs (RSPP) in Moscow, Russia, 09 February 2018. Photo: EPA-EFE/MAXIM SHIPENKOV

At the time, Romania was undergoing a fast-tracked process of privatization, boosted by preparations to join the EU. That’s how the Năstase Cabinet (PSD) ended up taking responsibility in Parliament in 2002 over the strategic decision to pass a number of assets into private hands, including enterprises in the metallurgy industry. For their most part, these were unprofitable companies the state was eager to get rid of, and the privatization wouldn’t cost the state much. This wasn’t the case with COS Târgoviște, which was still turning a profit (admittedly, a very small profit), but the state hadn’t clarified its criteria for privatizing a state-owned enterprise. As a result, a strategic plant such as COS Târgoviște, which was still a lucrative business with potential for further ramping up its profits, ended up being turned over to a Swiss offshore company called Conares Trading, which turned out to be a front for promoting Russian interests represented by the Mechel group. Conares Trading was originally set up by a close associate of Zyuzin, a little before the privatization of the Târgoviște steelworks started. Switzerland was chosen as a venue, since it was a favorite spot for Russian offshore companies.

It’s unclear how Conares Trading was awarded the privatization contract by the relevant Romanian authorities, to the detriment of the Turkish company Erdemir, which also placed a bid in the tender, all the more so as one of the criteria stipulated by the Romanian state, experience in the field of metallurgy, was rather difficult to meet by the Swiss offshore company.

It’s equally unclear how the privatization price was so low, especially if we consider the company’s assets. 77% of its shares were sold for 2 billion USD. Moreover, the Romanian state provided a number of exemptions in the form of delays and tax breaks to the company that was now controlled by the Conares Trading offshore company, which was representing the interests of Mechel, despite failing to observe the contractual terms for the privatization. And that was not all. The Romanian authorities were generous to the Russian investors, providing them with state aid worth 68 million USD in 2003 and 2004, which is five times what the steelworks had been earmarked for investments prior to the privatization. The terms of the privatization remain undisclosed, 20 years after the contract was signed by PSD officials in the Năstase Cabinet.

In the following period, Mechel expanded its business in Romania. In 2003, it took control of the Industria Sârmei Câmpia Turzii plant for merely 28 million USD. In 2008, it went up to purchase Ductil Steel Buzău, this time for 142 million EUR. The company had another smaller plant in Oțelu Roșu, which was also included in the deal. This time it was no longer a privatization, as the selling party was a private group of Italian investors. In 2010, using a Cyprus-based offshore company as a go-between, Mechel bought Laminorul Brăila, another metallurgical plant. The Russians paid 9,4 million EUR, at a time when Romania was struggling with the effects of the economic recession.

All these years, no state authority, whether it was the institutions handling the privatizations or those that were supposed to monitor the process, or the Competition Council, took notice or action to curb the Russians’ tendency of accumulating assets in the metallurgy sector. By 2010, Mechel now owned 80% of the market for reinforced concrete, the primary raw material used in rail works and construction, but also major shares of the Romanian market for other metallurgical products. Under the successive cabinets led by Năstase, Tăriceanu and Boc, the Mechel group expanded and consolidated its activity in the 2000s in Romania, while none of these governments, regardless of which side of the political spectrum they represented, did anything to stop its expanse.

Artboard: Veridica/Iulian Preda

Later on, the authorities realized it hadn’t been a good idea to provide a Russian oligarch with control over a strategic sector, for a number of reasons. First of all, his business interests are not aligned with Romania’s priorities, and when the business turns bad, the negative effects leave a huge dent in the economy. Secondly, this leads to an unhealthy dependency where a certain corporation ends up cornering the market for a certain raw material of strategic importance, something that goes against every regulation of a market economy.

Thirdly, as soon as the Russian oligarch falls out of favor with the Kremlin strongman, things will get worse real fast for the holding, with potential effects on investments in Romania as well. One such incident occurred in 2008, when Zyuzin was publicly accused by Vladimir Putin of operating higher prices on the Russian market compared to his export tariffs. Putin also made a number of veiled threats, causing a significant drop in Mechel shares, which revealed the full extent of how vulnerable Russian oligarchs are, and how constrained they are by a sophisticated and dangerously unpredictable power system.

The economic crisis of 2008 also hit hard Mechel’s dealings in Romania. In 2012, companies were cutting back most of their activity, and the Russians too started to think of ways to sell the plants in Romania. The steel production dropped by 15% overnight at national level, as a side note to the discussion about the vulnerability of key products in a faulty privatization strategy. Another shortcoming was the fact that the number of employees was cut drastically during the restructuring process.

The transfer of assets from Romania to Mechel entities followed a rather unorthodox pathway. Some of the plants in Mechel’s portfolio were sold to a micro business for the round sum of 52 EUR in 2013. The company in question, Invest Nikarom, was owned by the parents of the former Mechel representative in Romania, Olga Chumakov. Meanwhile, COS Târgoviște filed for insolvency in 2013 and went bankrupt in July, 2021. The matter was settled merely in 2022 in spring, when the steelworks was taken over by another Italian private company, Beltrame, in exchange for 38.3 million EU. The new owner promised to retool the business and resume activity. Time, money and jobs were lost in the process. Of the 14,000 employees on the company’s payroll in 1999, only 2,000 still worked in Mechel’s plants in 2014. Besides, the company’s assets were systematically plundered by the Russians. For instance, a line of production commissioned by the army, including a forge that was producing special steel for cannons, was dismantled and fully relocated to Russia.

Dmitry Pumpyansky, Putin’s lieutenant controlling the Romanian market for industrial pipes

Whereas in the case of Mechel things were settled once they withdrew from Romania at the end of a very public bankruptcy, the two other consortiums in question, operating in the industrial pipes and aluminum sectors, are a different story. The companies remain an important presence on the present-day Romanian market. Let’s next examine the Russian company TMK, which set up a holding with a dominant position in Romania in the field of industrial pipes. TMK is controlled by Dmitry Pumpyansky, an ardent supporter of Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin. The group he controls owns two factories in Romania: TMK Artrom in Slatina, producing the pipes, and TMK Reșița, a steelworks providing the former with raw materials. Overall, the two entities employ 2,500 workers.

Russian President Vladimir Putin (R) and Governor of Volgograd Region Nikolai Maksyuta(L) listen the explanations of Director General of the Trubnaya Metallurgical Company Dmitry Pumpyansky (C) during the visit to the Volzhsky Pipe Plant in Volgograd, Monday 19 February 2007. Photo: EPA/MIKHAIL KLIMENTYEV

TMK’s takeover of the Reșița plant sparked a great deal of controversy. The buyout followed a number of failed privatization attempts by an American company, Noble Ventures, which failed to abide by its contractual obligations. As a result, the contract was terminated, and in the end the Russians ended up buying the plant for a symbolic fee of 1 EUR in February, 2004. The privatization was operated by the Năstate government.

The issue with TMK was not faulty management, as the company continues to operate on the Romanian market. In the current context, however, with the Russian invasion in Ukraine, Pumpyansky, the owner and chairman of TMK, is one of the few hundred representatives of the Russian business and political elites that were included on the list of sanctions introduced by the European Union. Associating with an individual targeted by sanctions created major difficulties for TMK.

Pumpyansky’s assets, including his financial operations at TMK, got frozen. Under these circumstances, TMK Romania had to temporarily default on its payments in early March, being unable to pay any of its employees’ salaries. TMK employees and trade unions found themselves to be collateral victims and staged protests in Bucharest, calling on the Romanian authorities to offer a solution to break the deadlock. People on the TMK board who were handed sanctions by the EU, including Pumpyansky and his son, stepped down in early March and were replaced with individuals who had no such problems. Pumpyansky will very likely continue to call the shots, effectively managing the group and making key decisions, despite the shareholders’ legal loophole to keep TMK afloat.

Artboard: Veridica/Iulian Preda

Later on, on March 24, 2022, the National Fiscal Authority (ANAF) introduced a series of restrictions targeting TMK assets, however allowing the TMK holding to keep squaring up essential payments, such as employees’ salary rights, provider contracts or bank payments. Since the measure imposed by ANAF is only temporary, TMK employees in Romania started to protest again, creating the risk of pushing the company into total gridlock once again. When the legal solution offered by the Romanian state is expired in mid-June, the Ciucă Cabinet had to come up with another legal solution, thus adopting Emergency Decree 79/2022 in early June, allowing Russian companies subject to European sanctions to continue their activity without fully freezing their accounts, although their activity is expected to be closely monitored by representatives of the Romanian state.

The economic fallout from the TMK’s operational standstill reflects not just on the holding’s 2,500 employees. These companies play a rather important role horizontally, beyond their key position on the local market, affecting other sectors of the industry as well. Their clients include large companies to which they provide industrial pipes and other related products. The best-known of these is the carmaker Dacia, but there are other less visible or familiar names, which are no less important on the car and hydraulic markets, such as Nimet Târgoviște, ASO Chromsteel Târgoviște, Upruc Făgăraș or Branto București.

The Romanian Government passed another Emergency Decree, 36/2022, whereby it provided social protection measures to employees of companies affected by the Russian invasion of Ukraine, including sanctions imposed on companies from Russia and Belarus whose activity had been restricted or hampered due to the conflict. TMK is one of the prime candidates to benefit from this law, alongside its clients and suppliers. By the time the draft law was passed, the Government estimated as many as 30,000 employees of such companies could be affected by the developments in Ukraine. These people might benefit from compensatory wages under the government’s emergency decree.

Romania’s aluminum production, under Russia’s control

Another similar case is that of our third example in the heavy industry, more specifically the aluminum production sector, controlled by the Russian company Vimetco, whose main asset is the Alro Slatina manufacturing plant. The privatization of Arlo Slatina, the crown jewel of Romania’s aluminum production sector, was odd, to put it mildly. Marco International, a company that at first described itself as drawing American capital, was the one that took over the plant. As it later turned out, this was a shell company controlled by Russian oligarchs. A few years after the privatization, in 2007, the company was renamed Vimetco. It later transpired that Vimetco was a holding registered in the Netherlands, headquartered in Amsterdam, but owned by the Russians.

Marco gradually purchased chunks of Alro Slatina’s social capital, the company having already been listed on the stock exchange. Once the Russians reached a 41% company ownership share in May 2002, it became harder for the Romanian state to negotiate favorable privatization terms, since it was already very complicated to find a potential buyer – someone who was willing to invest in a company where the majority package was already owned by a shareholder. Therefore, the Government decided to sell a 10% share package to the largest private shareholder, which allowed Marco International to now own the majority package for merely 11.4 million USD. It was a very low price, considering that the Slatina-based aluminum manufacturer was a highly lucrative company in the early 2000s, not some budget black hole the state needed to plug at all costs.

Photo: Ischek, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Subsequently, the Romanian state accepted without much consideration that Alprom Slatina and Alum Tulcea, which supplied Alro with raw materials – aluminum oxide – should be turned over to Vimetco. That’s how the Russians created an integrated top-down system in this sector, which yields significantly higher profits. Concurrently, the downside was that Romania became dependent and vulnerable in a key economic sector that was monopolized by the Russians, just as we’ve noticed in the case of TMK.

Much like the owner of TMK, Vitaliy Machitski, the man who controls Vimetco and Alro Slatina, was himself targeted by sanctions imposed by the European Union in the wake of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, started in February, 2022. The difference is that, unlike TMK’s chairman, Machitski was more perceptive, which is another way of saying he was better informed, and transferred his share of Vimetco to other entities as early as December, 2021, which could not be traced back to him. In the case of TMK, the transfer occurred much later, in early March, 2022. Vitaliy Machitski’s son, Pavel, together with two other Russian oligarchs close to the family, later resigned from Alro Slatina’s board of administrators at the beginning of March, 2022, in order to eliminate element whatsoever that could link Alro Slatina to the Machitski family. Again, it’s a stretch to believe this disconnection is hardly anything else but an attempt to bypass EU sanctions. Just like TMK, Alro is a key asset of Romanian economy, and its Russian ownership can be considered a strategic vulnerability. To provide just a sample of how important Alro actually is for Romanian economy, it should be said that Alro is Romania’s largest electricity consumer, with a 6% share of the total input, as producing aluminum is a very electricity-hungry process. Of late, the plant has cut back its production activity by 60%, starting December, 2021, putting at risk the jobs of the approximately 3,000 employees of the group. Paradoxically, Alro was the victim of a string of events generated and influenced by the Russians themselves, namely the artificial increase in prices for electricity and natural gas, determined by Putin’s economic policies in connection to Europe, a situation that was amplified by the Russian invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022.

Most of Romania’s oil imports come from Russia or via pipelines transiting Russia

We can now move on to the third sector where Russia’s interests are “dangerously” well represented, which helps create a harmful dependency for Romania: oil and gas. The story of Russia’s involvement in the oil and gas market in Romania after the fall of communism in 1989 started rather early. In 1998, Lukoil, the second-largest oil company in Russia after Rosneft, bought the Ploiești-based Petrotel refinery, winning the privatization tender.

Russia at the time was awarded the contract to the detriment of the American company Conoco Philips. The controversial decision was taken by Victor Ciorbea’s Cabinet and president Emil Constantinescu. The Democratic Convention was the ruling party at the time after having won the 1996 elections.

The fee paid by Lukoil for an important asset of the Romanian oil and gas industry was symbolic, a meager 54 million USD. Lukoil went on to develop a strong network of filling stations, the third-largest on the Romanian market. On paper, its activity is not controlled by a Russian entity. The Russian investors set up an enterprise in the Netherlands, just as they did in the case of Vimetco. Its name is Lukoil Holdings BV. Therefore, the Russian company with the highest turnover in Romania is not listed in official records as registered in Russia, although it is controlled from there.

The war in Ukraine and the Western sanctions introduced in response to Russia’s attack are affecting Lukoil as well. Vagit Alkeperov, the Russian businessman who controlled the company for three decades, was forced to step down as president of the oil company after he was listed as one of the individuals sanctioned by several governments. What is more important is that the crude oil Lukoil is refining at the oil plant in Ploiești is imported from Russia. Since EU members decided to impose an embargo on Russian oil imports, Lukoil’s operations in Romania could be virtually gridlocked, as the company runs the risk of losing its source of raw material. There’s a period of transition of a few months allowing Lukoil Romania to comply with the new sanctions. It is unclear right now what the company’s strategy is for continuing its activity. Under these circumstances, Lukoil’s business model will encounter a number of challenges.

Lukoil President Vagit Alekperov (C-L) and Gazprom CEO Alexei Miller (C-R) attend a panel session titled 'Energy for Global Growth' during the Russian Energy Week in Moscow, Russia, 04 October 2017. Photo: EPA-EFE/MAXIM SHIPENKOV

Romania has four working refineries right now, of which only three are competitive on the market (the Vega Ploiești refinery, owned by Rompetrol, is very small, with a production capacity of merely 0.4 million tons). The largest refinery is Petromedia Năvodari, which has a production capacity of 6 million tons and is owned by Rompetrol. The second-largest refinery is Brazi, owned by OMV Petrom, with a maximum output of 5 million tons, while the refinery owned by Lukoil, Petrotel Ploiești is the third-largest on the market, with a production capacity of 2.5 million tons. In 2020, Romania was 68% dependent on Russian oil imports. This was way above the EU average of 96%, but it should be pointed out that Romania imports two thirds of its crude oil demand.

Since Lukoil has a market share of approximately 20% of Romania’s refined oil (Romania imports a third of its oil from Russia via Lukoil), the situation might pose a series of problems in terms of securing Romania’s crude oil supplies. From this point of view, the situation also creates vulnerabilities for another player on the market, Rompetrol. The owner of the most important refinery in Romania, Rompetrol is presently controlled by the Kazakh state-owned company KazMunayGas, which has access to a plentiful supply of oil from Kazakhstan. As a result, half of Romania’s crude oil is imported via Kazakhstan. The problem is that these crude oil imports, accounting for another third of Romania’s refining capacity, are transported via a pipeline called the Caspian Pipeline Consortium (CPC) which transits Russia.

The sanctions imposed on Russian oil imports by EU Member States do not affect imports from Kazakhstan, yet the risk in this context is that the Russians might block transports via the said pipeline. Therefore, at the end of March, the flow of oil exported through the CPC was suspended for a month, the Russian operator in the port of Novorossiysk in the Black Sea claiming in his official report that the terminal had been damaged in a storm. Consequently, even though it is not explicitly endangered by sanctions, the import of oil from Kazakhstan is vulnerable to these geopolitical developments, and might be blocked should the conflict between the Russians and the EU escalate, since it is transiting a pipeline on Russia’s territory.

Speaking of Lukoil, there was also another incident that might be labeled an act of asset fraud, similar to what happened in the case of Mechel. In 2014, Romanian prosecutors charged Lukoil of having caused a 1.7 billion EUR fraud to the national budget from its dealings with Litasco SA Geneva, Lukoil’s private fuel trader. The authorities even put a lien on part of Lukoil’s bank accounts, including its shares of Petrotel, as well as other sums of money belonging to Lukoil. The company was charged with tax evasion and money laundering. Prosecutors claimed Lukoil transferred the profits it reported in Romania to its subsidiaries in other countries in order to thus avoid paying the tax on profits.

A file picture dated 02 October 2014 shows a police vehicle entering a Lukoil's refinery near Ploiesti, some 60km north of Bucharest, Romania. Photo:

The Prime Minister at the time, Victor Ponta (PSD), defended Lukoil publicly against the prosecutors’ allegations, insisting on the importance of Lukoil as an economic operator that employed 3,500 people at local level. Despite the undisputable allegations included in the indictment in 2014, the investigation dragged on and eventually the company and its representatives evaded prosecution for their alleged crimes. What happened to the investigation all these years? It was referred from one court to another: the Prahova Tribunal issued two acquittal rulings, whereas the Ploiești Court of Appeal remanded the case for retrial after prosecutors appeal the original acquittal decision. The last retrial ruling in this judicial to-and-fro came in November, 2021. In February, 2022, the Prahova Tribunal extended the lien on Lukoil’s assets ordered in the original investigation, while the court case is still pending.

Using transfer pricing as a method of tax risk management, which is one the charges prosecutors presented Lukoil with, is not a practice restricted to Russian companies alone, and it’s probably commonly used by investors from other countries. This example underscores, however, another problem linked to Lukoil’s dealings in Romania, adding to the reasons why privatizing the Petrotel refinery back in 1998 may have not been the wisest decision.

Romania ended up importing gas from Gazprom, despite having the gas deposits needed to secure its energy independence

The Russian company Gazprom also operates on the Romanian oil and gas market. Gazprom entered the market relatively late, starting 2011. Meanwhile, it has built a network of 20 filling stations with the help of NIS Petrol, a Serbian company owned by the Russian energy giant. Gazprom managed to win the tender for a number of onshore oil and gas pockets in Timiș County. Using the same principles as other major Russian investors, Gazprom not only penetrated the market, but it was also allowed to expand in a number of directions and sectors.

With respect to the same company, Romania managed to expand its dependency on Russian companies to the field of natural gas as well, where Gazprom is the number one company on the Russian market. Although we have our own local resources of natural gas, something the majority of other EU Member States lack, the authorities’ inability of coming up with an investor-friendly legal framework, targeting the offshore deposits in the Black Sea in particular, in conjunction with the 20% drop in Romania’s onshore production capacity in the last four years, has led to an increase in the amount of gas imported from Russia, from a mere 2% in 2015, to 17% in 2020 and 26% in 2021. In terms of figures, in 2021 Romania produced approximately 8.6 billion cubic meters of gas, and consumed 12.3 billion. The difference of 3.7 billion was imported, according to data made public by the National Energy Regulatory Authority (ANRE), Romania paying approximately 1 billion USD for its gas imports. What is even more troubling is the fact that gas imports have gone up in recent years, and the price tripled over 2020-2021.

The only supplier of gas was Gazprom. Unlike most other European governments, the Romanian authorities negotiated a direct long-term contract with Gazprom. Ever since the early 2000s, Romania no longer engages in direct trade, and every transaction goes through intermediaries, who bring the gas from Russia to Romania. These intermediaries also claim a part of the profits, meaning the final price Romania has to pay for importing gas is much higher.

With regard to the way the Russians construe their strategy, it is interesting to note that one of the companies used as an intermediary to import Russian gas is owned by the same oligarch who controls Alro Slatina, one of the largest consumers of electricity in Romania. For a long time the company’s name was Conef, but now it’s called Imex Oil, the same company that acted as middleman for handling half of Romania’s Russian imports.

Whereas things are more complicated with oil, since we’re also talking about a natural process whereby resources dwindle and internal production shrinks, with natural gas we can say Romanian authorities virtually sabotaged themselves. Romania has enough reserves to cover its domestic gas demand for the next two decades. There are approximately 200 billion cubic meters of gas in the Black Sea, in areas that were auctioned off in the last two decades, but never moved on to the exploitation phase.

The main reason the exploitation was repeatedly postponed has to do with a number of decisions and laws adopted by the Romanian authorities in recent years. On the one hand, the decision-making trio Liviu Dragnea - Iulian Iancu - Darius Vâlcov holds a share of the responsibility. The three were behind the economic decisions targeting the energy sector during the PSD administration of 2017-2019. From this position of power, in 2018 PSD negotiated a legal framework for exploitation works with multinational companies operating in Romania that wanted to get involved. Passed with a view to regulating investments in offshore gas deposits, the Law 256/2018 virtually ended up blocking all operations in the area.

Since all projects were postponed or frozen, Romania lost not just time, but also a number of investors. Exxon Mobil, a major American company, renounced the largest gas deposit in the Black Sea, which it was supposed to exploit in equal shares jointly with OMV Petrom. The Americans’ share was bought by the Romanian state company Romgaz in exchange for 1 billion USD, the transaction being finalized in 2022 in spring.

Artboard: Veridica/Iulian Preda

On the other hand, although PNL took power in 2019, and the Liberal Energy Minister, Virgil Popescu, promised time and again that the law would be amended in order to unlock investments, it took two and a half years, from November 2019 until June, 2022, for that to happen. The law was recently modified and rehashed, the leaders of the ruling coalition made up of PSD, PNL and UDMR taking responsibility for it. It has the potential of greenlighting the Neptun Deep project, although the first gas will be extracted as early as 2027. Their exploitation will be key to cover domestic consumption and reduce Romania’s reliance on imports, against the backdrop of the waning onshore production.

Russia’s direct or indirect ploys in Romania: national rhetoric, controversial politicians and the authorities’ apathy

As a consequence of the political decisions of recent years, which more often than not reflected a nationalist ideology, projects aiming to exploit natural gas in the Black Sea were postponed. As domestic onshore production also went down, Romania had to up its volume of natural gas imports from Russia, which might cost us a lot in the new context created by the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

What is paradoxical about these decisions is that, although they didn’t serve Romania’s best interests, some of the people behind them continue to be promoted in key positions in the administration. Former PSD deputy, Iulian Iancu, described by a former colleague from PSD as “owned by Gazprom” according to the cables disclosed by Wikileaks, was nominated by PSD and voted by the current ruling coalition in a management position at ANRE, the national authority regulating the electricity and natural gas market in Romania. It should be said that, in 2019, president Klaus Iohannis refused to appoint Iulian Iancu as deputy-prime minister on economic affairs. He had been nominated by the then Prime Minister, Viorica Dăncilă (PSD). The president argued his appointment would be at odds with Romania’s Western orientation. Apparently, the authorities have now reconsidered Iancu’s standing.

With respect to offshore exploitation works and the related legal framework, this was not an isolated blunder on behalf of Romanian authorities. Another telling example is their inability of channeling significant investments in energy production. Since the state still owns 80% of the production capacity, the lack of investments in this field is another example of strategic mismanagement. This phenomenon, jointly with the diminishment of coal-based production due to enviroment-related reasons, has turned Romania into a net importer of electricity. The paradox, in this respect, is that part of the electricity is imported from Romania’s neighbors, which produce it using Russian gas. Therefore, our actual energy dependency on Russia is far larger than official records state, which at any rate don’t paint a rosy picture.

There’s one last example illustrating how Russia’s interests in the field of energy have prevailed and the Russians got what they wanted. I’m referring to Chevron’s plans to invest in shale gas exploitation in Pungești, Vrancea County. This initiative created a huge public scandal at the time. The ensuing street protests of October, 2013 prompted Chevron to leave Romania, although they had secured every legal permit required to advance their operation. Of course, there is no direct evidence of Russia being involved in this matter. Yet in this case the matter was settled suspiciously fast and abruptly, which is strinkingly similar to the authorities’ unresponsiveness to the various actions of Russian companies in key sectors, energy included. There have been rumors and speculation regarding a possible involvement of Russian agents instigating the wave of protests, and taking into account Russia’s modus operandi when it comes to hybrid warfare, Russia will stop at nothing to achieve its goals, which makes this hypothesis a genuine possibility.

Romanian environment activists are sitting on the pavement after they occupy the Triumph Arch Square during a demonstration, in Bucharest, Romania, against drilling for shale gas using the technique known as hydraulic fracturing or 'fracking', late 16 October 2013. Photo: EPA/ROBERT GHEMENT

The unfortunate conclusion is that, whenever there was Russian money or investment involved, the Russians always had a strategy, whereas the Romanians most of the times did not. What is more, at times the Romanians’ lack of strategy seemed to have aligned to and actually favored Russia’s interests. Romania’s dependency on Russia is not overarching or significant, mainly because historically and culturally, interactions between the two countries have never been strong, although relations are not as marginal or inconsequential as the myth disseminated in public discourse, particularly by the authorities, claims they are.

If the European-Russian divide deepens even further, Romania will be forced to stick to its European track, imposing the appropriate sanctions and banning all trade with Russia. Finally, it must be said that, considering the differences in terms of value and vision between the Western and European models Romania adheres to and Russian autocracy, curbing economic relations with Russia becomes a moral duty, not just an economic obligation or a security-related decision, particularly considering the war in Ukraine and the atrocities that were committed as part of this conflict.

Romania’s National Defense Strategy, adopted by Romania’s Parliament in June, 2020, refers to Russia and its aggressive actions in the region as one of the major threats to Romania’s security at present. It remains to be seen how this strategy will be implemented and what measures the authorities will take not just to counter these threats, but also to fix the problems created by past decisions that have incremented Russia’s presence in key sectors in Romania.