Serbia has been, for years, Russia’s closest ally in the Balkans. For Moscow, the relationship is a means to project an image of power and international relevance. Belgrade, on the other hand, plays the pro-Russian card to show that it has an alternative to a West that bruised its ego during the Kosovo war, but also for some pragmatic reasons, such as Russia’s support in the UN Security Council and its role as an energy provider. Belgrade’s real interests lie, however, with the EU, and the war in Ukraine may bring about a change – albeit a slow one – in its relationship with Russia.

For more than a month, Serbia has been the target of mass bomb threats. Pro-government tabloids and some high-ranking officials claim that the campaign has behind it the West and is connected to Belgrade’s reluctance to impose sanctions on Russia, while offering no proof for the allegations. However, Russia, or Serbia’s own intelligence services may as well be interested to launch such a campaign.

Vucic’s Serbian Progressive Party (SNS) got enough votes to easily form a government, with the Socialist Party of Serbia kept as a junior partner. However, President Vucic suggested that SNS may get a new coalition partner instead of the Socialists so, at the moment, the biggest uncertainty is who will form the government in Belgrade.

Russia has been trying for years to keep a foothold in the Western Balkans, especially through its connections with Serbia and Serb groups in the region. The war in Ukraine may now push Moscow’s allies closely in the Western camp.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has mostly been condemned in Europe and beyond. However, there are a handful of exception, and Moscow’s main ally in the Balkans, Serbia, is one of them. Officially Belgrade spoke in favor of Ukraine’s integrity, but sanctions or even a harsh condemnation of Moscow are out of the question. Moreover, the media – which is mostly under some sort of government control or influence – is unabashedly showing its support for Putin.

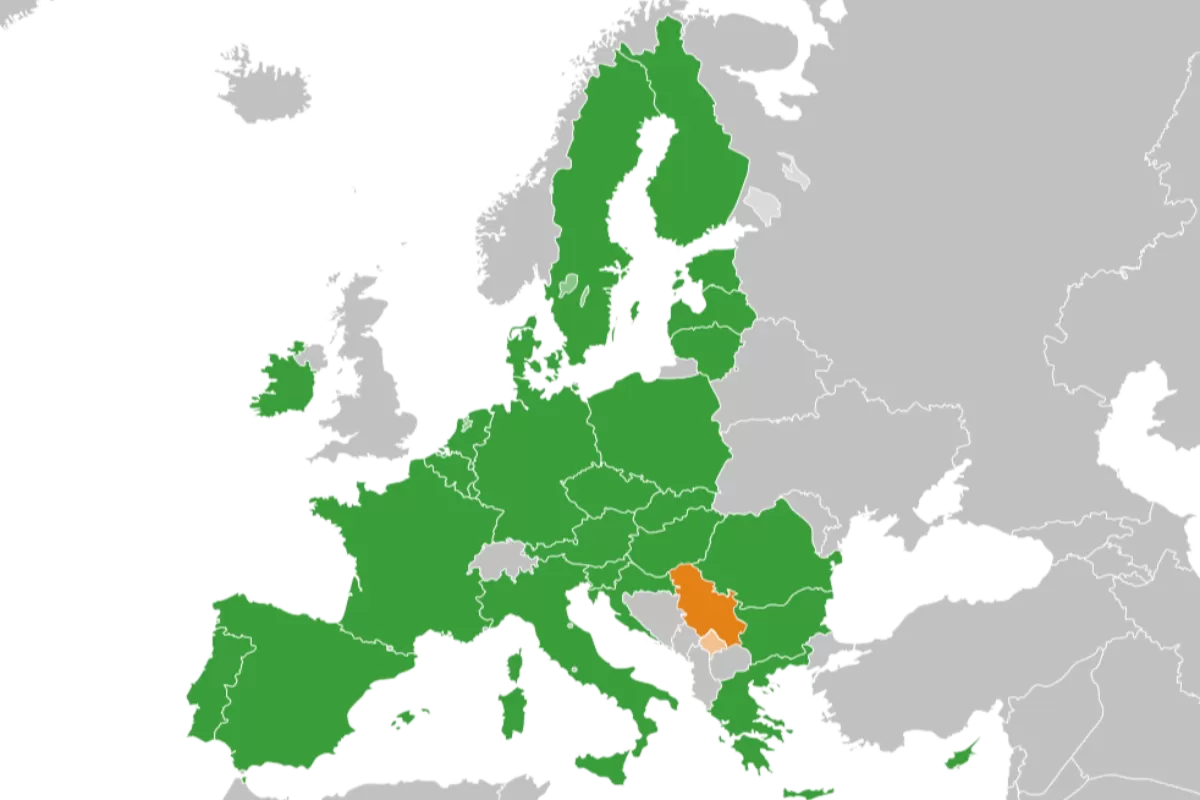

Countries in the Western Balkans have long expressed their desire to join the EU, but their inability to get through with the reforms required by Brussels, as well as the latter's hesitations, continue to prolong the pre-accession process. The answer to the stalemate could be a regional mini-Schengen.

One of the greatest athletes of today has become a symbol of the anti-vaxxer movement, but also a symbol of nationalists in Serbia. But is he really a nationalist? To what extent is the “nationalist Djokovic” a media creation? Is the best tennis player in the world a hostage of Serbian myths and nationalism?

The Djokovic scandal goes beyond sports or health policies. It is also an episode in Australia's internal political disputes and a pretext for self-victimization by anti-vaxxers and Serbian nationalists.

With elections looming in Serbia, the Vucic regime, which has an almost complete political and mediatic grip of the country, faced an unexpected challenge. Crowds mobilised for an environmental cause – and won.

Decades after the guns fell silent in Bosnia, a different type of war is being waged in Belgrade between those who insist on facing the past so that Serbia can move forward and those still trapped in the wartime nationalist narratives of the 1990s.

A Cold War era relic, the Non-Aligned Movement is still seen as useful by one of its founding members – Serbia – and a prospective new-comer, Russia. Both are aiming to project their soft power among the organizations 130+ members and observers. And both may be expecting too much from a Movement that never really managed to become a real alternative to the world’s power poles.

Outgoing German Chancellor Angela Merkel was, for years, the driving force behind Berlin’s – and EU’s – policies in the Western Balkans. As Merkel is exiting the scene, the region is still years away from EU integration, and some of its countries even took a turn away from their stated objectives of becoming consolidated liberal democracies.

Authoritarian states like Russia and China use the capital to increase their political clout. However, their investments and the loans they grant are not as advantageous as they are advertised, and one of their hidden costs is the undermining of democratic values and standards.

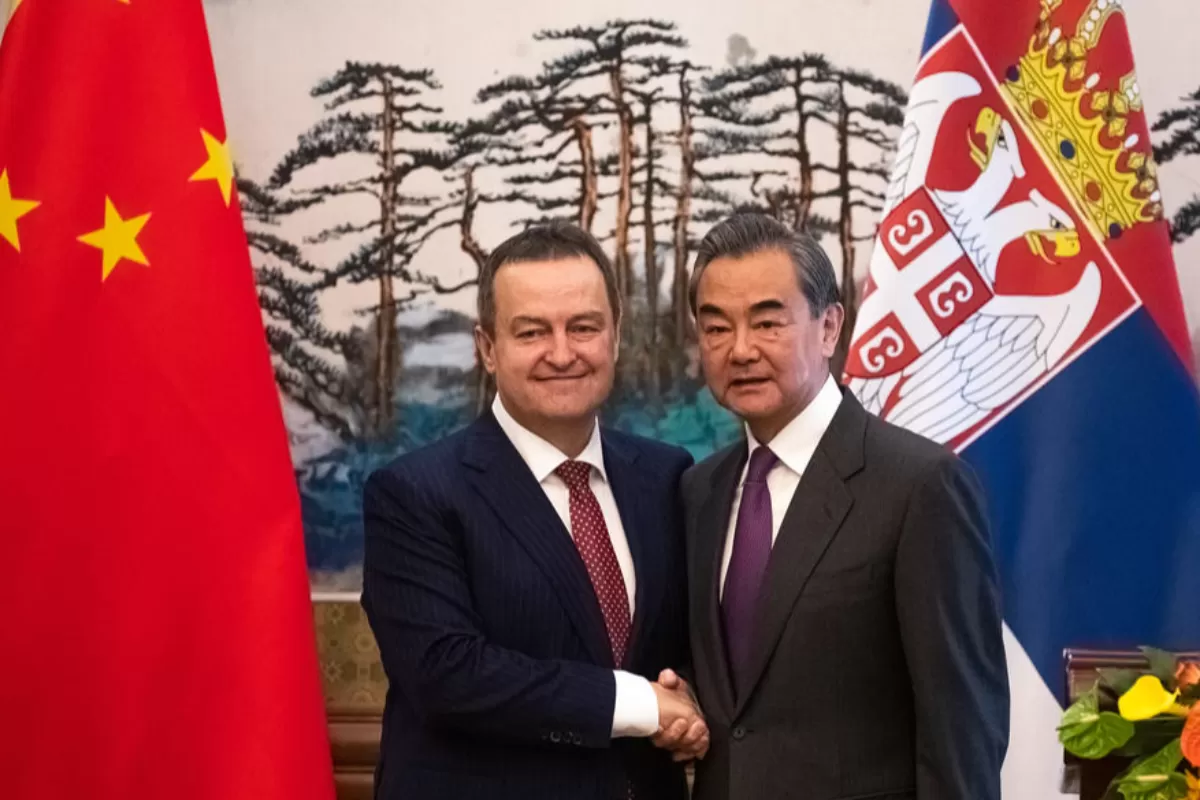

In the past few years, Chinese investments in Serbia have intensified, strengthening economic and strategic cooperation between the two countries. However, in addition to investing in production, new technologies, servicing old debts, some of these investments have brought with them harmful effects on the environment, but also a further collapse of the legal system and institutions.

The coronavirus pandemic has changed the world we live in, affecting our lives and habits. Changes are visible in every sphere of society, and every change has its impact on political trends and vice versa. On the one hand, the pandemic put the spotlight on science, medicine and technology. On the other hand, it also brought to the forefront conspiracy theorists and those who do not believe in the progress of medicine and science in the first place. The pandemic also lead to an increased activity of the far right which connected to the anti-vaxxer movement and conspiracy theories.

After tensions in the 1990s and the war in Kosovo, Belgrade's relations with NATO have fundamentally improved, as Serbia has sought to break out of the isolation of the Milosevic era. The partnership with NATO is a constant in Serbia's policy, but the relationship is only partially assumed: the authorities emphasize the country's neutrality, the media focuses on the much weaker cooperation with Russia, and the population sees no gain in a possible NATO integration.

Last year was a year of mask diplomacy, and 2021 is becoming a year of vaccine diplomacy. While the EU is struggling to procure and roll over the vaccines it needs for its citizens, Great Britain and Serbia (European countries, but non-EU members), are European leaders of vaccination.

Many Serbs do feel sympathetic towards Russia – after all, it’s the major power that has been constantly backing their claim over Kosovo – and their leaders often steer the media towards a negative coverage of the EU. However, most Serbs want their country to join the EU, and so do their leaders and the relevant political parties.

What makes Serbia interesting to anaylze when it comes to Russia's influence is the already formed pro-Russian public opinion. Therefore, the question arises whether Russia in Serbia has a need to invest in strengthening its influence when public opinion is already in its favor. It is enough to look at the cover pages of the Serbian daily press where you can often see Vladimir Putin, as well as the media reporting on Russia so you can get the impression that the pro-Russian narrative is possibly created by Serbian journalists and editors. It means that pro-Russian narrative is not sponsored or created by Kremlin.

The option for China is connected to Belgrade domestic and foreign policy objectives. As it seeks to show that it has an alternative to the West, Belgrade has chosen the more relevant power, which is on the rise, unlike a Russia marked by isolation and crisis. China, in its turn, is interested to have bridge help that would gain it backdoor access to the European markets.